How a month without computers changed me

Topics

Translations

No emails left for me to read. Nor write. I’ve sent a message to my family and delegated my open source projects (Autoprefixer and PostCSS) to my friends. With my last tweet sent, I turn off my laptop, phone, and tablet. My Digital Sabbath begins in 10 minutes: no digital devices for the next month.

From the days of the Butlerian Jihad when “thinking machines” had been wiped from most of the universe, computers had inspired distrust.

— Dune Messiah

On the left are things from my old, digital life—carefully, I turned them off, got together and put into a bag. What I got myself for the new life is on the right.

The month of Ramadan

It began with a post about the Islamic month of Ramadan, when one is not allowed to drink or eat until “the first star appears in the sky” (imagine how difficult it must be fasting like that in Norway, during the polar day). The Ambassador explained that religious people deny themselves what everyday life has to offer to understand how great God’s grace is. This idea gave birth in my imagination to a technocratic state where people do without soy and genetically modified foods for a year just to see: natural agriculture is costly and might lead to global hunger.

Then I asked myself if “technological fasting” could do one good in modern society. Technology has changed the world in the blink of an eye, leaving us no time to reflect on it. What if a month without modern technology could “travel” you to the past? What if there is a way you could compare your technology-relying self to what you once were?

I had doubts. My love of IT and addiction to digital overload were not going to make it easy. But then I learned about this effort of a computer-weary The Verge journalist. My life, he wrote, had become so much better without the computers. To me, his report seemed not without bias, and I decided to take my own journey into the pre-digital world—this time to be seen through the eyes of a programmer.

The preparation

Doing without my laptop was not gonna cut it, I thought. Smart chips being now used in every domain of life, I must use no digital device at all. I read about fasting in other religions and decided to make precise rules to guide me through whatever difficulty arises. In its final form, my covenant was, “you must not operate any device that stores a programme in its memory”—in other words, no von Neumann architecture-based devices were allowed.

This was the criterion I used to prepare for my journey. Just like a James Bond, only the other way round: the small, shiny, and functional gadgets gave way to things old, cumbersome and one-purpose. Thanks to the hipsters, this vintage could easily be found in flea markets.

My friends tried to scare me away from taking the journey by telling the tale of the Mozilla programmer whom two months of life without the internet made him delete his twitter account.

To burn all the bridges, I told everyone about my Digital Sabbath plans. Doing any work during that time was out of the question, so I took a leave and explained to my colleagues how to contact my girlfriend in case of emergency.

Evil Martians played a trick on me though, by deciding to run an internal competition with prizes for the biggest open source contributions exactly during my Sabbath month.

But there was no going back. My fasting began on November 6, 2013.

The photography

For my forced dive into the world of analog photography, I picked a light-meter equipped Zenit-122. My camera would take care of the process—I only needed to keep turning the dials until it told me everything was alright. While most cameras make the focus right using special split screen and microprism to align the two sides of an image, a light-meter is a small solar cell and three LEDs that are seen in the right side of the viewfinder. The upper one is lit if your photo is going to be too dark, the lower if too light, and the middle one turns green if the options are set in the right way.

It was not that hard taking pictures, but I understood it was the computers that had made photography such an easy-to-do, everyday thing. Of course, even our parents didn’t do it the hard way—they didn’t need to know chemistry or develop the photos. Yet, analog photography reminded me of driving: you start with theory, then they show you what to do and how, and then you practice in a place without other cars. It is not until you have developed the skill that you go and take actual photos. With digital photography, everyone is a photographer now. It only takes opening your phone app; even a child can do that.

Another discovery I made was the incredible power that modern digital cameras have gained in the last decade. Before the Digital Sabbath, we got stuck at the Ukrainian border, where we witnessed the wonderful tradition of putting a whole lot of candles in graveyards during All Saints’ Day. At night we took many a wonderful picture without using a tripod—all thanks to the immense light sensitivity and optical stabilizers that modern cameras have. It was no use carrying my analog camera at night: the photo film is 30 times less light-sensitive, and in semi-darkness there is no taking any half-decent photo without a tripod.

If I saw a rapidly developing event, I would not even bother to take out the camera—each photo demanding two parameters (focus and exposure time) set, I would not be fast enough to take one.

But at the same time, I felt film to be a blessing a disguise. Modern cameras are too powerful. You push the button—you get the photo you need, always. As a result, not only do you stop thinking about the how but also about the what. Film is hard to use, film makes you find a way. Analyzing all the parameters and options available makes a good warm-up exercise for your brain: you start looking for a better angle or composition.

The grain and warm colors that film has are all the rage now. But personally, I didn’t see any real magic in them. That’s just what photos had been back in the days. Our parents were younger, and we were kids—we get nostalgic, of course. Exactly like pixel art is just the style of games childhood from our childhood. It doesn’t make a game better per se. Will our children value the effects produced by a bad phone matrix, a reminder of their warm past, as high as we do the grain and warm colors?

My Digital Sabbath made me realize I would use my phone, not my big-ass digital camera, to take photos in my travels. I understood I had no need for the extra options it offered.

The watch

For the Digital Sabbath, I bought a Raketa (Rocket) soviet mechanical watch. Pity I didn’t manage to find a special 24-hour face version for polar explorers and divers.

In my opinion, each era has a technology that serves as its symbol. The mechanical watch is the crown of the industrial era. The technology was not developed enough for portable devices to be precise, yet people did everything in their might—used their ingenuity, diligence, and skill—to make the most of whatever they had. They did manage to make a watch based on pure mechanics. They used gimmickry such as having small rubies in the mechanism to decrease tension. That was why it was not until the advent of synthetic rubies that watches became cheaper and available to the general public at the beginning of the 20th century.

My mechanical watch was like a small living creature—its heartbeat kept reminding me it was fragile and needed proper care. For your watch to work for long and show precise time, you need to wind it up every day at exactly the same time. I expected this necessity to turn into a burden, but it didn’t. On the contrary, this nice little duty gave me the opportunity to feel the passing of time better.

Most importantly, time had become somewhat inaccurate. Contemporary quartz watches have a tiny error of a second per day. Synchronizing via the internet, computers, and phones don’t accumulate even that much error. It means we really are used to our watches being accurate. When we get to the railway station, and there are five minutes left before the departure, we can be absolutely sure we will make it.

A mechanical watch accumulates an error of up to a minute per day. It means your train may have already left the station because during the week the error has grown as big as five minutes. My watch having an unknown error was getting on my nerves throughout my travel, so I was always looking for sources of the exact time to adjust my watch to.

Unfortunately, one day, my watch simply stopped, never to work again—no surprise, taking into account how old it was. It is indeed nice carrying a small mechanical life on your wrist; nevertheless, I went to a shop and bought myself a quartz watch (by that time I already knew there was no computer inside it, only simple electronics and mechanics). I do love my time exact; I can’t do anything about it.

Yet I liked having a watch on my wrist. This childhood feeling had been long forgotten, and I was positively surprised that a watch did help you control the time. It is so much easier to take a look at your hand than to put your phone out of your pocket.

After the Digital Sabbath, I decided to buy a smartwatch like Pebble or Android Wear.

The map and the compass

The technology that is the symbol of our era? I would say, GPS and GLONASS. On the one hand, they use the most advanced things one can imagine—rockets to take satellites to the orbit, quantum physics to produce atomic clocks for the satellites, Einstein’s theory of relativity to compensate for the loss of time due to speed and gravity, computers to make complex calculations. On the other hand, unlike other brainy things easy-to-use maps are something that everyone on Earth needs. Satellites provide exact coordinates to every person, in any part of the planet, for free—so long as he or she has a cheap receiver.

But during the Digital Sabbath, when I visited a new town, I would have to find a newspaper stand, buy a map and then closely read the names of the streets.

During my preparation, I bought a compass. Primarily for the sake of the warm analog style. But it actually proved itself useful—so long as you at least know the direction of the street you walk along, it will make reading the map easier.

I didn’t have much difficulty using a GPS-less, paper map. Moreover, paper maps have their advantages, too: which one can be easily drawn and written upon—a digital or a paper one?

The notepad

During my trip, I found an old church with old Cyrillic calligraphy. It impressed me so much that I then created @linguopunk account on Twitter for calligraphies like it.

I wouldn’t have taken any pleasure in my Digital Sabbath if it wasn’t for the small spiral-bound notepad I bought to carry in my shirt pocket. It’s not that I had much choice either: digital life had degraded my memory, and I needed an external device to make notes in.

Honestly, I don’t consider the bad memory the younger generations have to be that big of a problem. True, we have to search for information all over again, but it might be a good thing. Information is so quick to change now. What you learned yesterday might have already become all wrong today, while bad memory has you find the latest, most accurate data every time.

I liked using the notepad. You always have a pen to spin in times of idleness. Unlike the touch displays that most phones have, a notepad provides for quick drawings. Another thing I liked was that everything you did at a certain moment was in the same place. The computer makes you follow a hierarchy that is alien to you: one application to search for video, and another for notes. In the notepad, there is only one timeline.

The thoughts

Boredom was the thing that scared me the most, so I did a lot of preparation: took a few thick books, drew up a schedule (when I leave one place for another) and made up several evening rituals to follow every day. The internet-less reality turned out to be a boredom-less one, too. Recreation does not require anything special—in the end, you can always go out and hunt for good photos.

On the very first day, I went to bed early and woke up early—my biorhythms adjusted to the Sun in no time.

Your battery is never low if you don’t have one. Nor will the rain ever ruin your expensive phone. I always had time to think everything over and always felt the pleasant sensation of doing the right thing at the right time. My heart was filled with bliss and confidence.

But soon I saw the difference between IT and other technologies. For example, a lack of electricity or water supply results in immediate discomfort. The internet does not—take a look at our grandparents, who do perfectly fine without computers. Yet without the internet, you sometimes feel so painfully nostalgic that it seems as if you have left your hometown and old friends and reminisce how good it was there.

Digital technologies are something more than routine tools we use without thought. The digital world has grown into our souls, creating whole new worlds for our imagination and creativity, introduced us to so many people we would have never met otherwise—without us noticing it.

The digital world needed no neuro-interfaces or cyberpunk-books to become part of us. The most painful thing about my Digital Sabbath was the feeling of something missing deep down inside.

I came to the conclusion that IT hadn’t changed the world around, but created another, a parallel one. The reason we are always nervous and never have enough time is that we are living two lives now. It’s without a doubt difficult, yet how interesting it is to be living two times as much!

By the middle of the month, I felt low—so big was my desire to code. It seemed I was wasting time instead of doing anything useful. When the pain was too bad, I would tell myself the story of _why, an iconic person in the Ruby community. One day he disappeared from the internet, deleting all his vast contribution to the world of open source. His final tweet was “programming is rather thankless. u see your works become replaced by superior ones in a year. unable to run at all in a few more”.

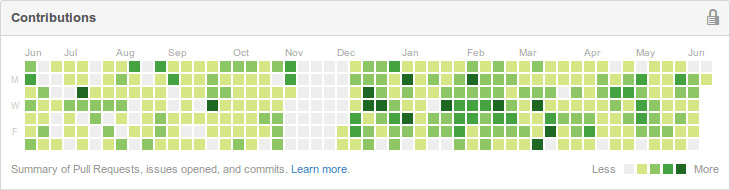

My Digital Sabbath was in November, as it can be seen from the GitHub contribution graph.

A little later, my anguish and longing faded into the background, but I got a feeling of my personality dissolving. The internet allows us to express our I much more clearly and intensely. We listen to music that we ourselves find interesting—it doesn’t matter if there are hardly any people in the world that like the same thing. We can pursue hobbies rare yet intimate. The ability to communicate with anyone, beyond the boundaries of your city, results in relationships with people as congenial as it ever gets. But this all pales in comparison to the opportunities IT gives us in the domain of creativity, a person’s brightest form expression. Time spent without the internet returned me to my school days: you could only listen to whatever music you happened to get and read books that were available in the local store. My personality seemed to be merging with society, majority opinion, and popular music.

The other side of being calm was a loss of motivation. The internet gets you to do things. You see the successes of other people and try to keep up with them. You value time much more dearly, as you know that any extra 10 minutes you can steal is a chanсe to read an interesting article from your archives that might produce a small change in you.

My Digital Sabbath made me re-evaluate my attitude towards social networks. Everyone knows that likes and statuses are no real communication. But when you are far from the place you live in, real communication is impossible. In a few weeks, I started to miss my friends and relatives badly. It is true that in the modern world we rarely manage to find time for a heart-to-heart talk, but the little actions and pieces of information from Twitter and Facebook at least give us a connection to others, no matter how small. I may not know all the details, but I keep track of the lives of my school friends from another city. I do know about the most important things in their lives.

Most importantly, social networks allowed for a new stratum, people who are always on the road, to develop. It’s not that people hadn’t moved to other countries before, but those had been a rare case. Even moving to another city meant having no close friends for a year or so, just because it would take time for your new friends to become close. Changing cities every month would mean having no close communication. Now, you can live far from home and yet feel a certain thread connecting you to your close ones. That’s why there are so many more people traveling non-stop nowadays. Citizens of no particular country. Almost everywhere in Asia or Europe, I meet my friends and acquaintances who are living there just at the moment.

What a strange thing—computers are nothing but little devices solving small-scale, mundane problems for us, but without them, I would be a completely different person.

The end

It is December 6, 2013. A month has passed, and my Digital Sabbath is over. My excitement has kept me awake for the last 24 hours. There are hundreds of letters and thousands of RSS news waiting for me. I’m so emotional and busy I will not have more than four hours’ sleep a day, for the next three days, and instantly become a night owl, again. Yet I will be so glad to have returned.

The conclusion

The “analog” world didn’t feel that much special and spiritual. The internet is not unlike a new flat—it seems empty and lacking soul. Not because the old one was better, but because the old one simply had many things to bring back good memories. The digital world is soon to get filled with our feelings. Just give it a little time.

Despite the fact I am not going to do another month without the computers, I liked my Digital Sabbath. A month was too much, though. Two weeks would have done just fine. I changed my attitude towards technology and the impact it has on society. I overcame my fear of boredom and now can easily take a cruise or visit places where there is no internet. I stopped worrying I never had enough time—it had become a logical thing, as I understood that with the internet, I live two lives in parallel. I stopped getting fancy with the quality of photography. Taking pictures with my phone is good enough, I decided. I also bought a watch—smart, not mechanical, though.

I would not recommend digital fasting to everyone, but a temporary abstinence of some sort seems a very right thing to do. All religions have compulsory fasting. Abstinence from meat in Christianity, or refraining from work in Judaism (btw, see eruv). The one I like the most is the keeping of silence in Hinduism, for example, Mahatma Gandhi would be silent one day a week: he would be reading, thinking, or writing.

It doesn’t take us much time to get used to a way of living and start doing things on autopilot. Our brain likes to save energy, so it turns our extremely voracious conscience as soon as it understands that everyday life can be done without it. As a result, our perception gets dull and replaced by thoughtless habits. Not letting it happen requires leaving the comfort zone, requires entering a new world, where you don’t know anything and have to start from scratch. You could take up a new hobby each month. Or travel from one city to another. Or do without things you are so used to, like having conversations or using computers—just for a little while.

Translated from Russian by Yaroslav Shtyrbu.