Normalization, consistency, and Clowne

One year ago we introduced a new flexible gem for cloning complex models, Clowne, with the support for the two most popular Ruby ORMs: ActiveRecord and Sequel.

Clowne was extracted from a large-scale Rails project we at Evil Martians were working on at that time. We were using it to clone the core record (aka God object) of the app—a single cloning operation could affect more than thirty different models. You can imagine how many relations existed between them and why we had to build a new gem to help us.

We open sourced Clowne once it seemed to be a feature-complete solution with all the flexibility and customizability we intended (following the principles from the GemCheck).

But, as it usually happens, the business had another point of view: requests for new, sophisticated features arrived, and we had to reconsider our cloning architecture.

Today, I would like to share some of the problems that forced us to start working on the new (1.0) version of the clowne gem and discuss some questions around database schema, e.g., data normalization and consistency.

In the beginning, there was a database

One of the tasks a backend developer working on a web application faces is the database schema design. Database schema describes how we store our business data model, and for many situations, there could be multiple ways of doing that. How to know which one to choose? How to compare or evaluate them?

Let’s take a look back into history.

Normalization is our friend

In 1970 a true landmark paper for the future of databases came out: “A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks.” In this paper, English computer scientist Edgar F. Codd described a relational model which later formed the basis of the SQL language development.

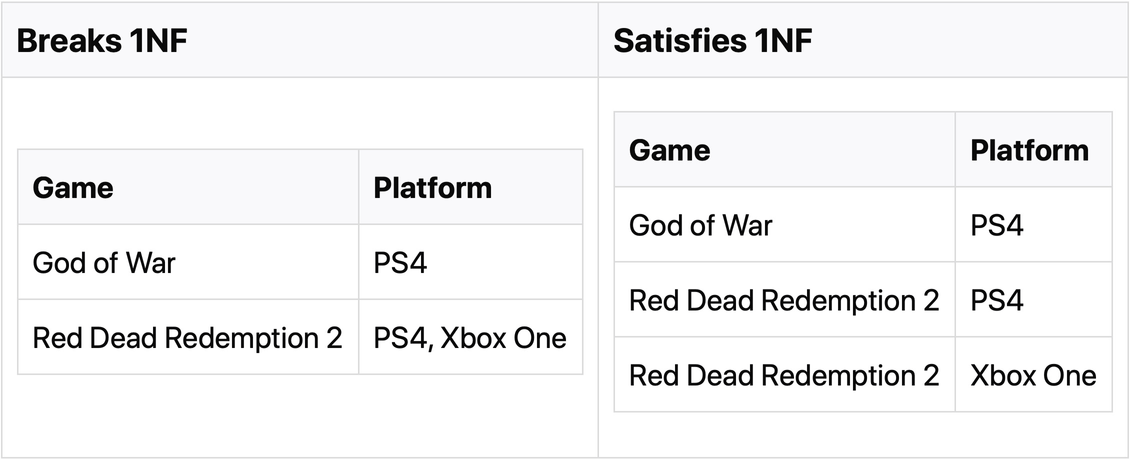

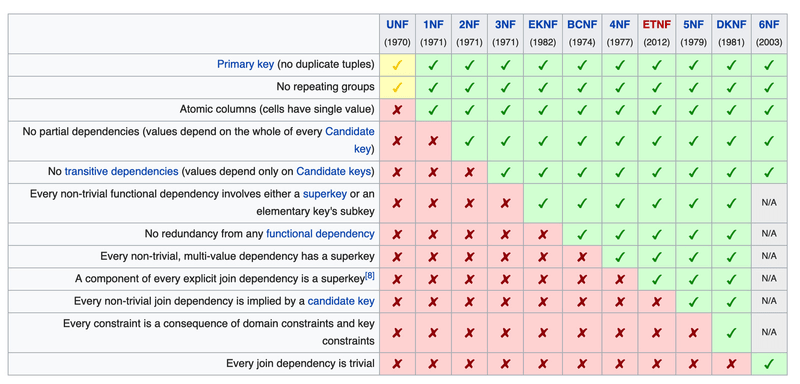

The integral part of this relational model is the process of structuring database relations. Edgar F. Codd called this process Database Normalization, and nowadays there exist six major concepts of normalization: the first normal form (1NF), the second normal form (2NF), etc.

It’s worth noting that compliance with each normal form is harder to achieve than with the previous one. For example, to satisfy the 1NF, you just need to follow the rule that each attribute (column) contains only atomic (indivisible) values:

And to understand the last one, 6NF, in-depth knowledge of relational algebra is required 👨🎓

Why is normalization important?

The primary goal of database normalization is to reduce data redundancy and improve data integrity. An additional advantage of normalization is an increase in data consistency. From the simple examples of normalization violation, you may notice that the basic normalization technique is the decomposition of database schema: divide larger tables into smaller ones and link them using relationships.

NOTE: Database normalization process is progressive, which means that if you have achieved a certain level of normalization, your schema also satisfies all previous levels (e.g., if the database has 4NF, it also has 1NF, 2NF, and 3NF).

Denormalization is also our friend, though cunning

Another technique we often use is denormalization. As the name suggests, it’s orthogonal to the normalization process of duplicating data in the database, usually, for the sake of performance (conscious way) or to fix some existing schema issues (legacy way).

For example, in PostgreSQL we can use unstructured types like json, jsonb, and array to duplicate the data and improve the read operations performance by getting rid of multiple JOIN-s. This approach is compelling, and in this case, a violation of normalization is justified.

On the other hand, real-world applications show us that database designs aren’t always perfect: a project’s requirements change fast, we lose sight of something, we have legacy problems left by the previous developers, or we have too much data to use the right solution (=normalization).

Unfortunately, normalization errors are not rare, and we will show you how easy it is to make a mistake while choosing the right solution. Let’s practice!

Selling products

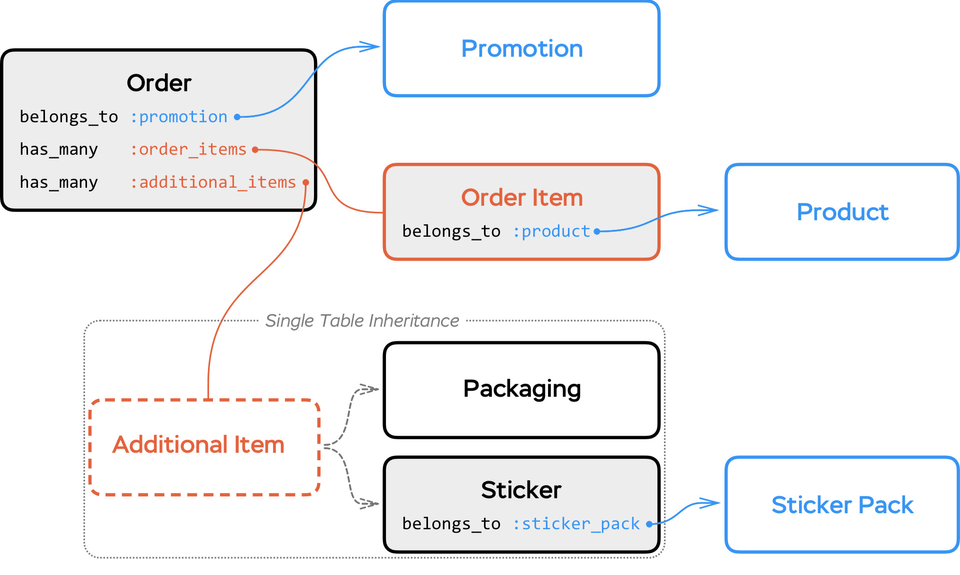

Let’s say that you are working for a business that wants to use your application to sell its products. We’ll start with a simple database structure that we used in the first article:

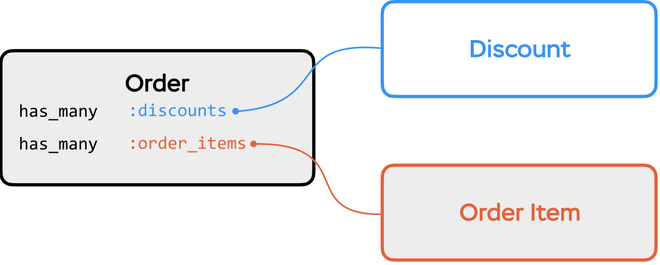

Let’s add a new feature that allows discounts on orders:

Our code to calculate the order’s total price looks like this:

class Order < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :order_items

has_many :discounts

def total

total_discount = discounts.sum(:percent)

PriceCalculator.call(order_items.sum(&:total), total_discount)

end

end

class OrderItem < ActiveRecord::Base

def total

count * price_cents

end

end

class PriceCalculator

def self.call(price, discount)

return 0 if discount >= 100

price * (100 - discount) / 100

end

endThis design is straightforward and satisfies all the normal forms. Let’s see how to implement cloning of the Order model.

Remember the Clowne

Since we already know about the powerful Ruby cloning library called Clowne, we decide to go with it for this feature:

class OrderCloner < Clowne::Cloner

include_associations :order_items, :discounts

end

# using:

# clone = OrderCloner.call(Order.first)Just a single line of code and we can clone an order with the associated records. Easy-peasy, isn’t it?

Everyone makes mistakes

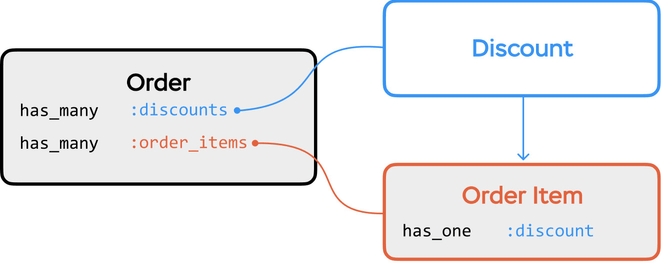

Your product grows, and one day you receive a new feature request from the business: “We want to be able to give discounts not only on the order total but on specific order items, too.”

Hm, we already have the Discount model in our app, so we just need to change it to work with OrderItems, too:

class AddOrderItemIdToDiscounts < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

add_column :discounts, :order_item_id, :integer

end

endAnd update the OrderItem#total method:

class OrderItem < ActiveRecord::Base

has_one :discount # new

def total

# was: count * price_cents

PriceCalculator.call(count * price_cents, discount&.percent || 0)

end

end

We haven’t changed the OrderCloner class, and at first glance, everything looks good:

# prepare order

order = Order.create

order_item = order.order_items.create(total_price: 100_00, count: 2)

order.discounts.create(percent: 20) # for all order

order.discounts.create(percent: 10, order_item_id: order_item.id) # for order_item

# check clone order result

operation = OrderCloner.call(order)

operation.persist

clone = operation.to_record

clone.discounts.count == order.discounts.count &&

clone.order_items.count == order.order_items.count

# => trueBeing satisfied with this concise and elegant solution, you deploy the code to production.

Angry customers 👿

Days go by. You calmly work on new tasks, and one day, a bug report comes to your mailbox—users are complaining about incorrect order prices. But you haven’t touched the order price calculation code for a long, long time!

You check the reported orders, and it looks like the price is correct, why are users saying the opposite?

Then you notice that all the “incorrect orders” are clones, so you decide to run a console and check the prices manually:

# are used instances from previous code snippet

order.total

# => 14400 // ((100 * 2) * 0.9) * 0.8

clone.total

# => 16000

Back to normalization

Let’s see what the final discounts table looks like:

CREATE TABLE "discounts" (

"id" INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT NOT NULL,

"order_id" integer NOT NULL,

"order_item_id" integer,

"percent" integer DEFAULT 0 NOT NULL

);There are only four columns, and yet we are breaking the 3NF. How?

A table satisfying the third normal form (3NF) is a table in 2NF that has no transitive dependencies (Wikipedia)

Let’s take a look at the dependencies we have in our discounts table:

• order_id -> order_item_id # thought the `order_items` table

# (order_items.order_id -> order_items.id)

• order_item_id -> id

• order_id -> id # transitive dependency!The dependency between order_item_id and order_id is defined outside of the discounts table (because OrderItem belongs to Order via the order_items table) and, of course, it doesn’t depend on the discounts primary key. So, we duplicated this dependency, and that’s what could be causing inconsistency in the data (which happens during the cloning operation):

discount = order.order_items.first.discount

cloned_discount = clone.order_items.first.discount

discount.id == cloned_discount.id

# => false

discount.order_item_id == cloned_discount.order_item_id

# => true // sic!The discount in the cloned record and the original both refer to the same order_item because we copied the order_item_id attribute as is. How can we avoid this problem and fix it?

(The best) option #1: satisfy 3NF

Let’s normalize our table—decompose into two tables:

CREATE TABLE "order_discounts" (

"id" INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT NOT NULL,

"order_id" integer NOT NULL,

"percent" integer DEFAULT 0 NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE "order_items_discounts" (

"id" INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT NOT NULL,

"order_item_id" integer NOT NULL,

"percent" integer DEFAULT 0 NOT NULL

);class Order < ActiveRecord::Base

# Orders::Discount placed in app/models/orders/discount.rb

has_many :discounts, class_name: 'Orders::Discount'

end

class OrderItem < ActiveRecord::Base

# OrderItems::Discount placed in app/models/order_items/discount.rb

has_one :discount, class_name: 'OrderItems::Discount'

endYes, these tables look very similar; and, yes, we need to change our cloning code to handle two new associations (and DRY-lovers’ eyes might start twitching at this point 🧐). That’s the price we pay to keep our data consistent: it would be impossible to allow incorrect discount rows by design.

Why not use Active Record polymorphic associations for this pretty similar

Discountmodels? There is a good reason why: polymorphic associations always break normal forms and sacrifice database consistency. See Don’t use polymorphic associations for critical data for more.

Even though this option is the best one (and we advise you always to approach it this way first), sometimes it’s not applicable: for example, if you’re using jsonb columns to store denormalized data (to improve querying performance by avoiding multiple JOIN-s). Another example, as we said in the very beginning, is working with a legacy database with a large amount of data, when it’s easy to shoot yourself in the foot while changing the schema.

Let’s consider the alternatives.

Option #2: patch at the application level

In our project, we had a very complex cloning case (more than thirty models involved) and some historical problems with the database schema.

That’s why we fell back to the second option: solve the inconsistency at the application level (i.e., write some Ruby code).

We relied on some business model-specific heuristics to restore the relations:

class CentralSuperFixer

def self.call(_origin, clone)

clone.discounts.find_each do |clone_discount|

# wrong_order_item produced by clone operation

wrong_order_item = clone_discount.order_item

# use product_id attribute as indirect sign

# to find the correct order_item

correct_order_item =

clone.order_items.detect { |i| i.product_id == wrong_order_item.product_id }

# fix clone_discount

clone_discount.update_attributes!(order_item_id: correct_order_item.id)

end

end

end

# call cloner and fixer altogether

clone = OrderCloner.call(order).tap(&:persist!).to_record

CentralSuperFixer.call(order, clone)This approach has many cons:

- Not 100% accurate (e.g., when we have two order_items with the same

product_id) - Hard to maintain both the application code and tests (easy to forget to cover the edge cases)

- It just looks ugly 🙁

Option #3: patch at the database level

Relational databases (e.g., PostgreSQL and MySQL) do not allow us to add a constraint to check values from the remote table (otherwise we could restrict discounts rows values based on the order_items table data) but we can add the custom triggers and implement pretty much any logic with their help.

We’re not going to dig deep into this topic: it has its cons, too (e.g., testing, performance overhead) and, in general, it’s not recommended to implement business logic at the database level.

You can find an example of such a trigger on StackOverflow.

Option #4: use the latest version of Clowne!

We went with the second option first and later decided to extract from the application code and add to the clowne gem.

Finding a better, generalized, solution and API took some time, and eventually, we came up with the two new features: the after_persist callback and a mapper.

Let’s see them in action!

# We only need to update the `DiscountCloner`

class DiscountCloner < Clowne::Cloner

after_persist do |origin_discount, clone_discount, mapper:|

# mapper allows you to get the origin of any record involved in the

# cloning process;

# we don't need to apply our specific heuristics anymore

order_item = mapper.clone_of(origin_discount.order_item)

clone_discount.update(order_item_id: order_item.id)

end

end

# let's try to run our cloner

operation = OrderCloner.call(order)

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

# by default cloner call is not wrapped into a transaction

operation.persist!

end

cloned = operation.to_record

order.total == cloned.total

# => true // yay!That’s all! Since v1.0 Clowne remembers the connection between all the original and cloned records during the cloning operation and a :mapper in the after_persist callback provides the #clone_of method to get this information. No more custom patches (e.g., like the ones we used in CentralSuperFixer)!

NOTE: It wasn’t possible to add this feature without introducing a minor breaking change. See the migration guide if you use an older Clowne version.

Here we have described only one way of using the new features, there are other uses:

- the

after_persistcallback allows you to manipulate with the just-cloned object after it has been persisted - the mapper data can be used as the log of cloning operation.

The updated, more flexible, architecture would also allow us to ship new awesome features in the future. There is always room for improvement in OSS projects!

Who wins?

We can say without a doubt that keeping data consistent and normalized is the best option. However, normalization is not a silver bullet (spoiler: there are no silver bullets), and sometimes we are forced to turn to other, darker, sides.

Keep your mind open, evaluate all the possibilities, and try to fix the database architecture problems (if any) as early as possible!