Finding growth: how to hack eBaymag with Growth Hacking

In this article, Evil Martians are auditioning for the part of Mythbusters show and destroying the myth that Growth Hacking is a controversial practice based on dark patterns. We have discovered an extremely practical and fair way to use it for engineering processes. Having been tested for several months on the official eBay project, eBaymag, it brought real revenue boost and development resources savings. Busted! 2 Growth Hackers and 0 dark patterns applied.

Growth Hacking, a technique to attain exponential growth for business results, today is a catchword with reams of articles written on the topic that has locked horns with traditional methodologies. The reason for that is simple: while Growth Hacking was evolving from the exclusive method of tech startups to the widespread approach, it accumulated many myths and unscrupulous practices.

One thinks it’s a set of out-of-the-box services with an instant effect, while the others feel certain it promotes “dark patterns” in product design. These are nasty tricks like airlines’ algorithms to let families sit together for an extra cost or barriers for subscription services cancellation.

You cannot just cancel your subscription without contacting support (adobe.com)

We don’t want this bad publicity to scare off developers, designers, and business owners. Evil Martians consider Growth Hacking as a good practice for task prioritization, saving resources, and bringing tangible business results that don’t cost a fortune. The practice does a good job at all stages of a product life cycle, from MVP to mature application to boost revenue or to pivot.

We use it to accelerate business results for several projects, and in this article, we’ll show the approach efficiency on eBaymag, an official B2B service to enforce local sellers’ trading volumes by distributing their items to international markets. We started to tap into Growth Hacking in late 2019, and now we are ready to share some insights and hints to help engineering teams and businesses to boost product metrics even under severe resources constraints.

Analyze, then prioritize

In a down economy, some businesses experience a surge in demand, while others fight to keep the lights on. Both of them face the emergency of rebuilding processes and redistributing engineering resources. But the real challenge is to choose the feasible business strategy and prioritize tasks amidst thousands of ways to win users and revenue.

Most product engineering teams have to deal with one of two ways of prioritization:

- Traditional development approaches prescribe to frame a constantly refillable backlog of tasks for features design. It ensures stability and predictability for long-term planning, shaping continuous process: complete the current task, take the next one.

- Alternatively, teams have Product Owners behind the scenes to prioritize features from the roadmap, according to the personal or corporate vision.

Software engineers typically understand a flourishing product as a product with rich functionality. Business owners often share this misunderstanding. (Not) surprisingly, more implemented product features do not add proportionally more users or revenue. That moment any business realizes the absence of positive correlation, it usually finds itself at a crossroads with loads of ways to attract new users.

A methodology of task prioritization that doesn’t dominate but works in parallel with regular development processes is crucial here. Teams need to select precisely the features that will bring more value and, at the same time, find resources for this gold mining while contributing to overall product development. Martian and eBaymag teams found this balance in Growth Hacking.

eBaymag: erasing barriers for sellers

Starting from 2016, Martians have been a core tech team behind eBaymag, covering all the technical areas. Three years later, Martians immersed themselves in Growth Hacking.

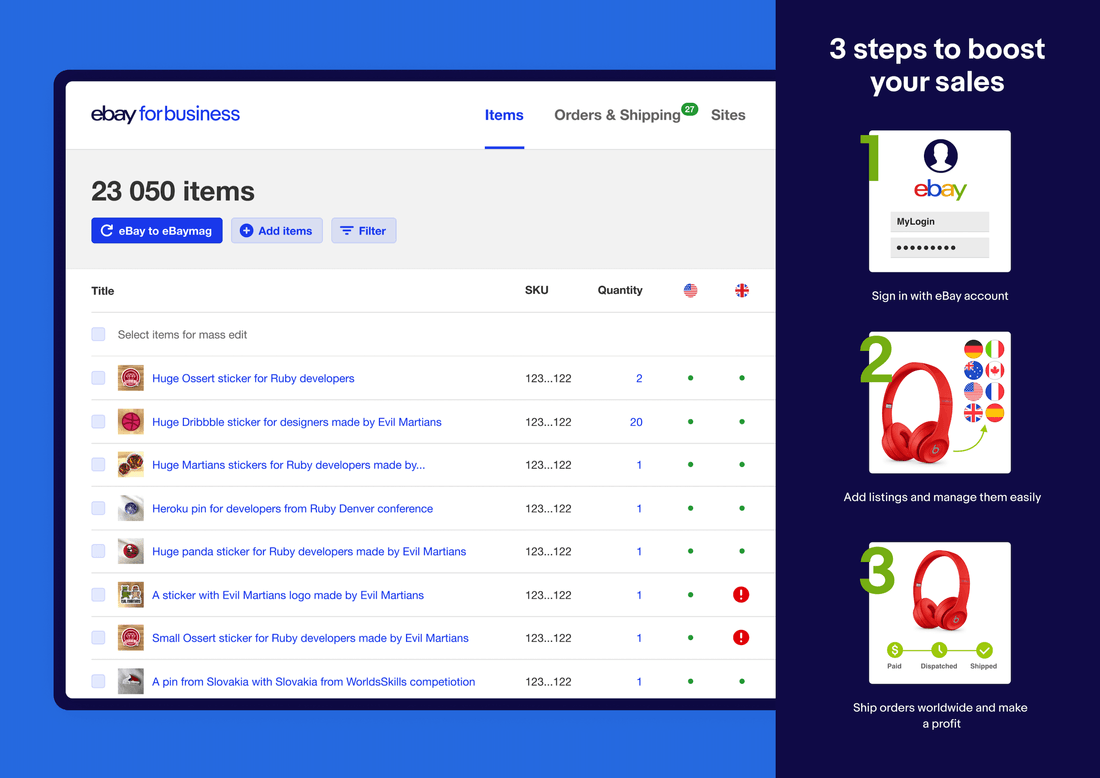

eBay supports local markets and SMEs: non-local products are available to users from any geography, but they have lower ranks and are thus shown accordingly in search results. eBaymag allows sellers to “hack” this algorithm, getting all the local benefits. Simply put, sellers in a few clicks export their products from one international eBay site to another (e.g., from eBay.com to eBay.fr or eBay.de) as local ones, with automatic translation of items descriptions, prices in local currencies, delivery by local services, and higher positions in search results.

For over 4 years, Martians were in charge of all product areas for eBaymag—assumptions and analytics, discussing and planning features, user interface design, backend and frontend development, infrastructure, deployment, and DevOps support. For the first three years, our primary goal was to rapidly evolve the platform by reworking, enhancing, and polishing the product and everything around it, bringing the culture of rapid changes and hypothesis testing. All that prepared a friendly environment for the next stage.

Starting to growth-hack

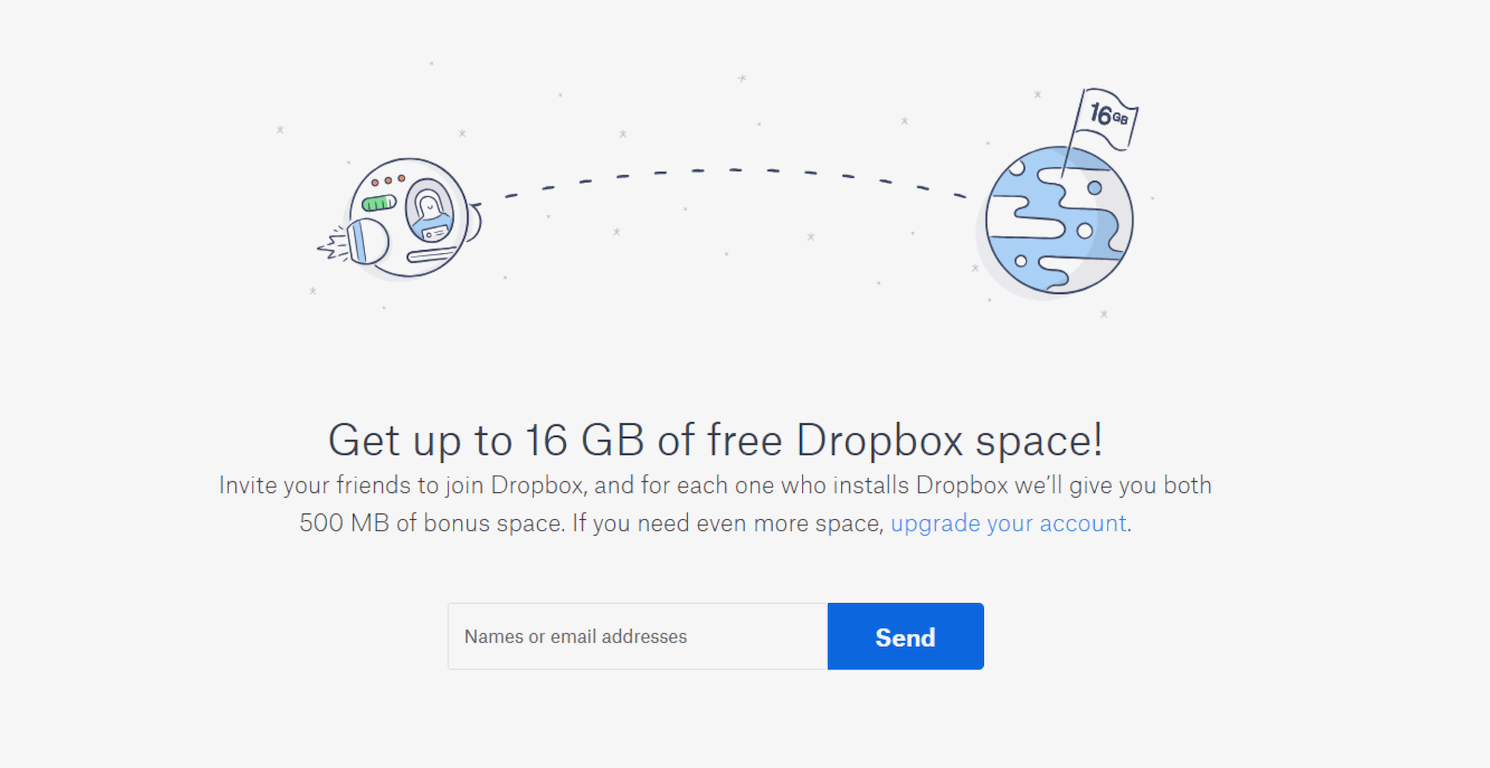

In its early days, the giant technology startups were obsessed with that new Growth Hacking conception. Sean Ellis, the Dropbox’s first in-house marketing specialist and the Growth Hacking mastermind, “hacked” the audience with just one trick: he gave users a gigabyte bonus for inviting friends with referral links.

One of the first “growth hacks” (dropbox.com)

Businesses like Airbnb, PayPal, Dropbox, and Microsoft tried this approach to expand their client bases. And eBay wasn’t the exception. Martians first utilize Growth Hacking for another eBay spin-off—the eBay Bonus project. It brought some encouraging results—experiments boosted conversions for some critical funnels, so that was time to use it again.

Experimenting

The main Growth Hacking differentiator from other product development processes is its fail-fast principle that arrived (stop the music!) from software development. Today, this is a new class of developers and product owners, for which the best code or design is the one that gives higher conversion.

Instead of immediate and detailed killer feature planning, they do research or run a short experiment. Thus, everything that doesn’t get enough confirmation on the first stage can be instantly canceled.

Let’s have a closer look at some Martians’ experiments and their results.

Experiment Examples

Make it worse

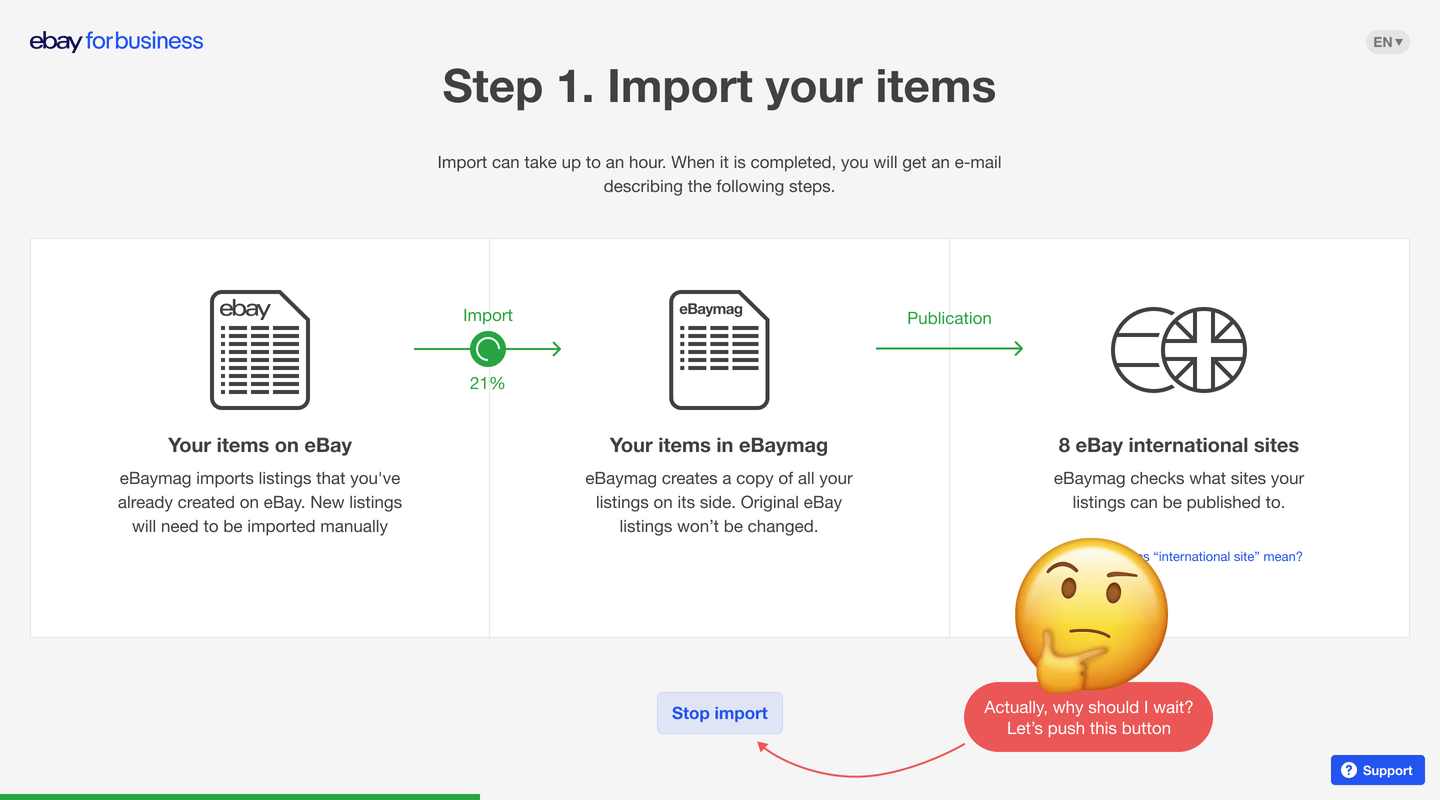

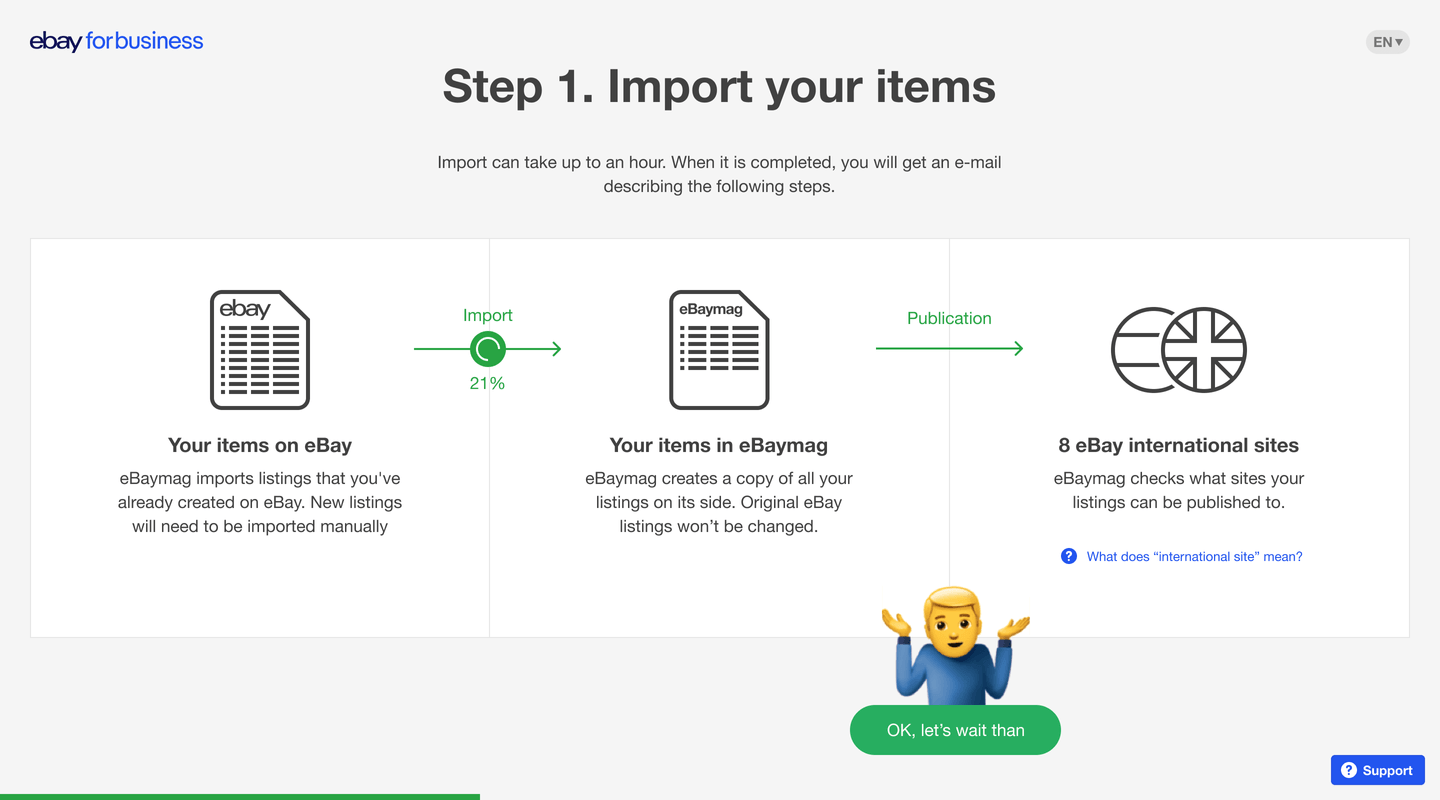

One of the first things people try in Growth Hacking is an experiment aiming to make something worse. We attempted to “degrade” item import in eBaymag, nevertheless, keeping the import workflow in order.

To distribute items to local eBay sites, a seller should import them first. But in the case of API architecture, we have to deal with thousands and thousands of data streams. Each item has a massive amount of contiguous data to exchange between sites—description, product images, limits, permits to be sold in particular countries, and many others. Combined with significant time for API to process the request, the import could take ages, especially for sellers with thousands of items. We always promised to send a notification, then the importing process completed, but some sellers couldn’t help clicking the “Stop import” button fiercely to switch to the main interface faster.

Earlier, you could stop import any time and not list any items

In the period from the moment import started and until users pushed the stopping button, we managed to import only around a dozen random items. In the worst-case scenario, there were zero items imported, and a seller could leave eBaymag without publishing anything. As a result, we couldn’t get best-selling products for local markets. In any traditional approach, we should rewrite the importing service to make it faster. Growth Hacking forces us to validate the idea first. Therefore, we completely removed the “Stop import” button from a panel keeping an eye on effect.

No button, no problems

So, import had no alternative but to be completed. We examined all the final data and confirmed that it was a critical bottleneck. We found a direct correlation: if all the items were imported, the chances to publish at least a couple of them raised by 14%. We scaled: we returned that “Stop import” button, but it was shown only 2 minutes after import started (according to our data, this was enough to upload a significant part of the items). And only then we redeveloped the import service itself to process faster.

No code!

The next type of experiment is an experiment without coding that saved us months of work.

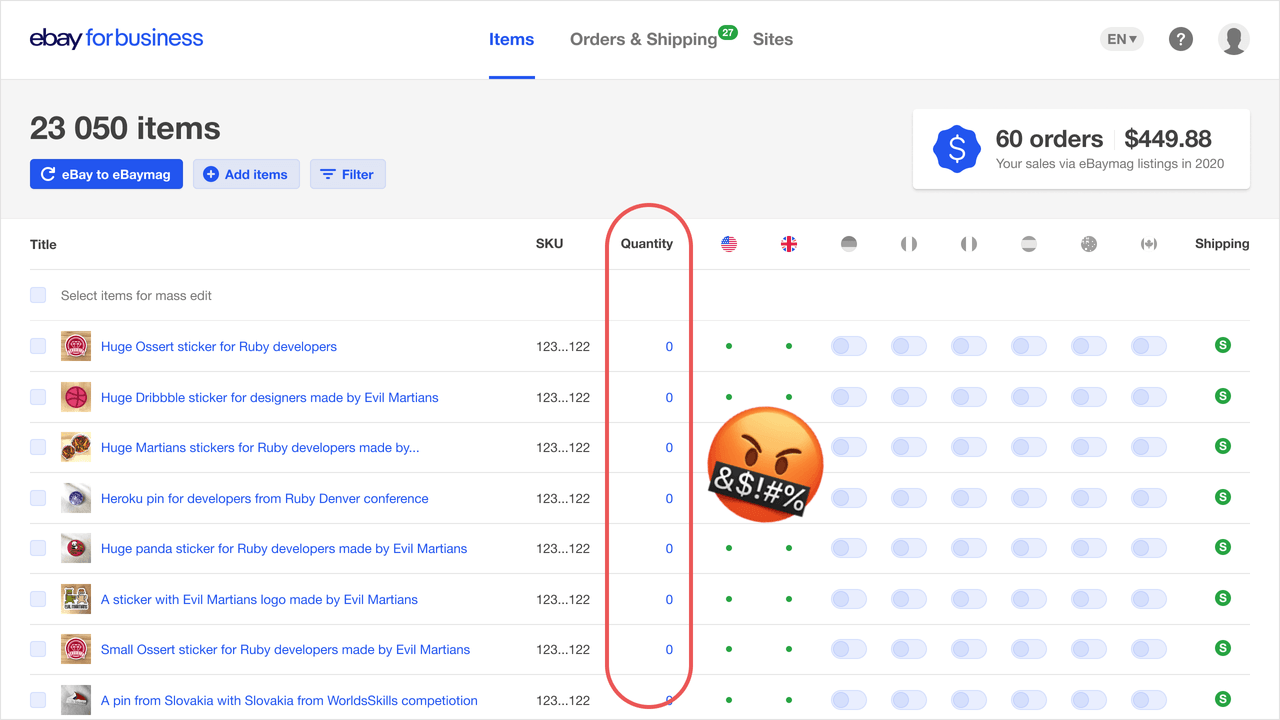

With eBaymag, sellers can distribute their products to eight different local eBay sites. But how to synchronize stock balances between them? How to understand which product is sold out and which one is in stock again up to time?

Good products are always sold out

For all the deployments, we use public eBay API. This kind of architecture assumes certain restrictions for some resources like the number of eBay API calls per a certain period and estimated time of completion. Balance synchronization was a slow operation since we had tens of API requests for each product, while a seller could have over 1,000 products at a time. We had two options—either to change the architecture or to consume the available resources more wisely.

The first way—the extension of the resources—required a large-scale update in the entire application architecture. We assessed this change in several months of development, taking into account all the related risks of new errors. Therefore, traditional methodologies dictated to postpone the task month by month.

With Growth Hacking, we decided to choose another way, starting with a manual experiment. We selected 50 sellers that often had sold-outs and were manually synchronizing their stock balances for a couple of weeks without changing our codebase.

In a nutshell, balance synchronization revealed the most benefits for a small but profitable segment of sellers with regularly updated stocks. We scaled it this way: Martians created an algorithm to search for sellers of this type and then synchronize their items. This small feature became one of our most successful experiments and led eBaymag to a surge in sales

Experiment with no experiment

Some hypotheses can be proved without any experiments at the low-key review stage.

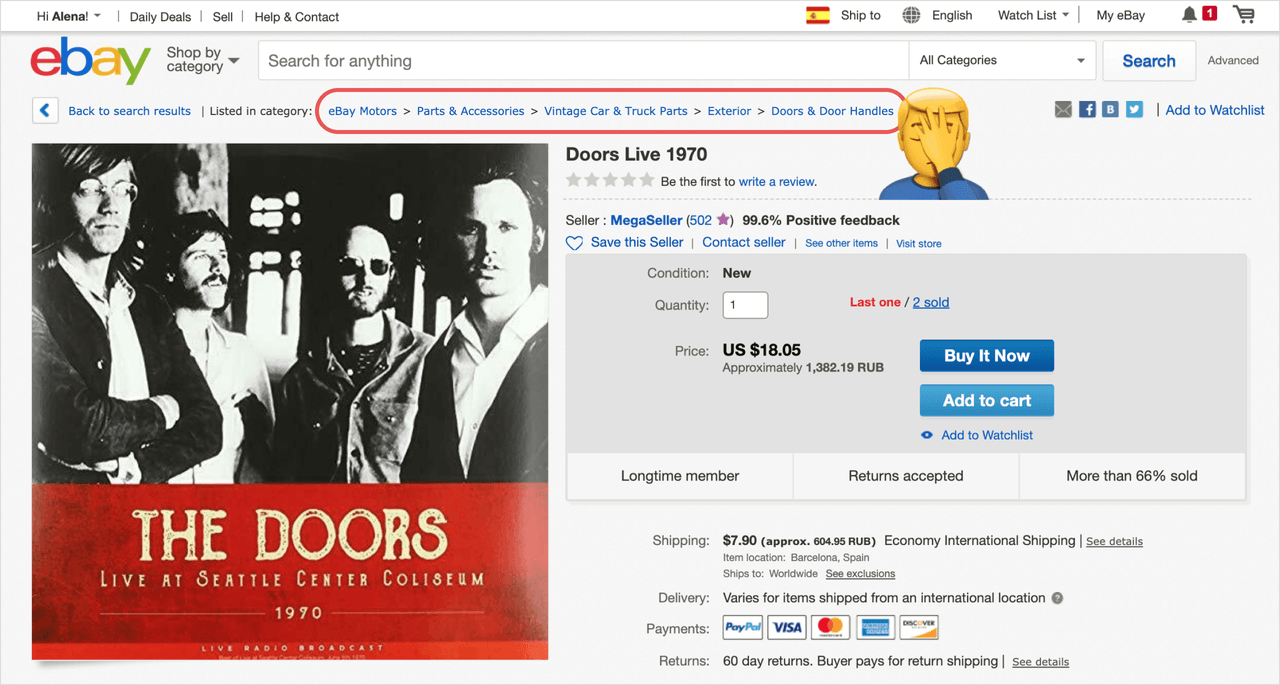

For instance, you can’t just copy some items from one eBay website and paste them to another without selecting a product category. In most cases, selecting a category is a no-brainer: their tree circuits on different sites are usually the same, or we manage to choose a category based on product name and description. But every once in a while, we lose.

Any category is better than none, right?

In the traditional paradigm, we would solve the problem by writing an advanced machine learning algorithm for categories selection. With Growth Hacking, we started with a precise question: what kind of profit did we lose due to category selection errors?

We analyzed several sellers who had this kind of error and revealed that most of them were inexperienced sellers with uninformative product descriptions. That was why existing selection algorithms, based on an item name and description, didn’t work correctly if they were poor and scarce. Accordingly, the overall turnover of such sellers was also low since poorly described products granted the lowest priority in search. Thus, no coding required.

Epic fail

Failed experiments in Growth Hacking have the same value as successful ones as we can get some valuable insights for cutting off weak growth areas. Here is an example.

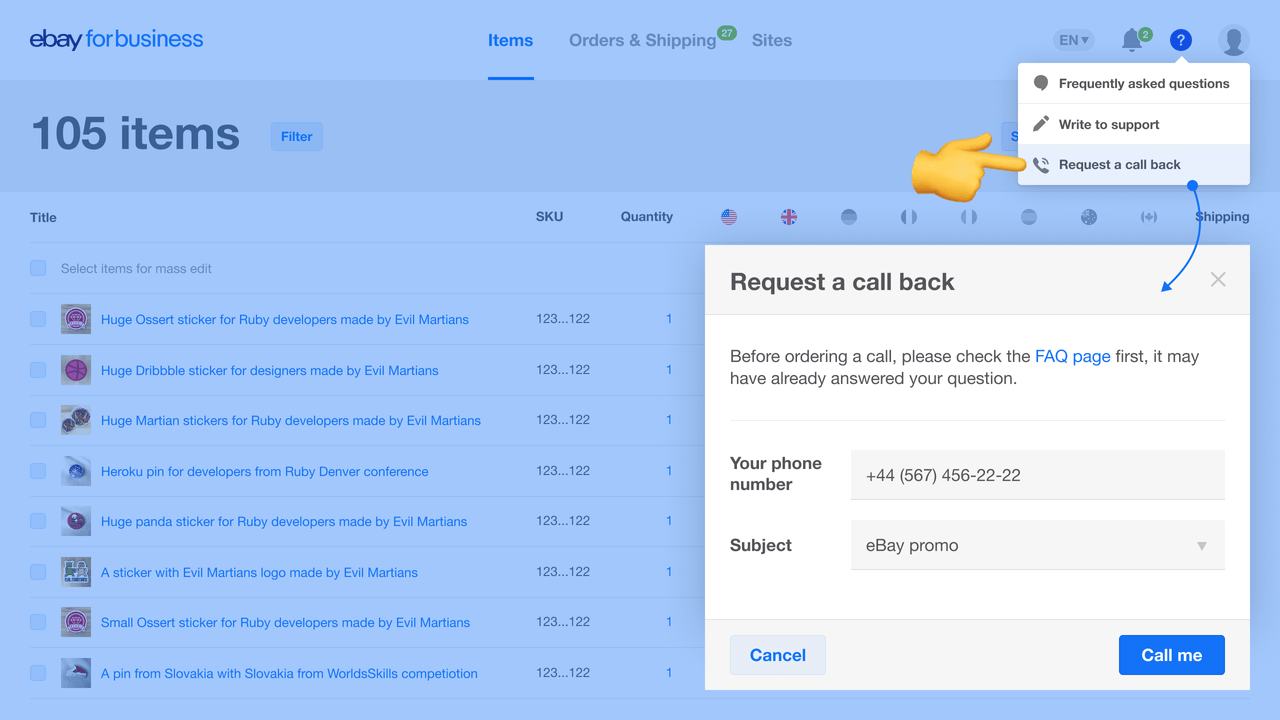

How to reduce the churn rate and attract more new users? We assumed that many people do not like to dig into interface options or pass through the onboarding process but prefer a real person to call them with all the explanations. So we added a “Request a call back” button to the Help menu section.

With a call or a user manual, please help me!

Eventually, after a month of experimenting, only 1.4% of new users requested a call, and we saw almost no effect on their retention. But we got other crucial insight in the process. 69% of the audience that visited the Help menu went purposely to read FAQ instead of calling or emailing a support service. Moreover, 73% of users failed to complete the “Request a call back” form because they followed the FAQ link and found all they needed there.

When users are eager to solve any problem, they’d better have other variants to find an answer as soon as possible than just waiting on a tech support call. With this insight, we reworked the Help Center section and extended it with guidelines and a simple search. The current results look promising: churn rate decreased by 10% as fewer new users leave the service. Besides, we now have less (by 20%) new account cancellations due to the reason “It was too difficult to manage.”

Experiments stats

Growth Hacking has already shown us its effectiveness being applied accurately and patiently. In eight months, we completed 68 experiments and researches. 25 of them were successful in giving a project new directions for business development and engineering. At the same time, the rest helped to eliminate the features showing little promise that saved eBay tons of resources, and increased the revenue with no dark patterns applied.

How to build your own Growth Hacking: hints and processes

How did we organize our Growth Hacking processes to work like this? Let’s skip through the list of the most crucial areas. We hope you will find here some useful information to do it on your own.

Defining key metrics

The goal of growth hackers is to boost product metrics like revenue, monthly/daily active users (MAU/DAU), and net income. The most critical is a North Star—a key metric that reflects the product values most precisely. For Airbnb, North Star is the number of apartment bookings, for Facebook—the number of active users per day. Sean Ellis defined a growth hacker as “a person whose true north is growth.” In other words, if we approach our North Star, we do it right.

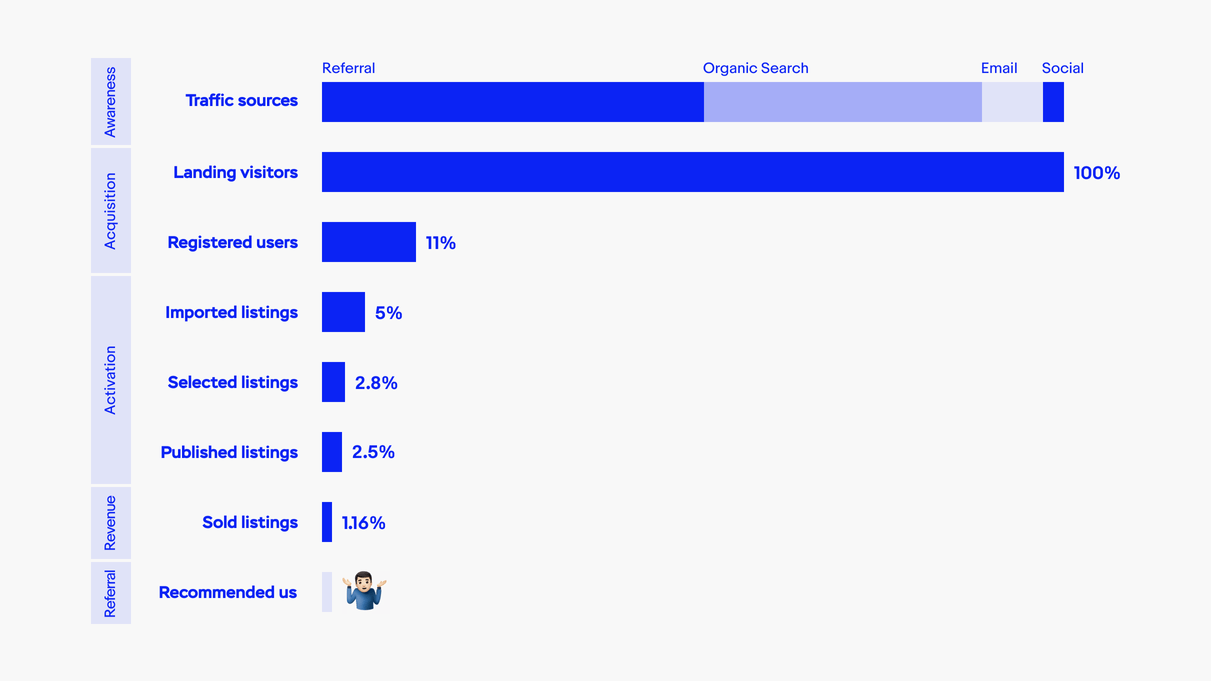

Once we started using Growth Hacking, we acquired an additional optimization direction for all our engineering processes: product growth capacity. That helped our team identify reference points for product enhancement. We began to measure every feature in terms of approaching our North Star metric—the total value of all orders received by sellers. We drilled into all the aspects according to the pirate funnel—we looked for bottlenecks and resolved them all the way down from the first user’s acquaintance with a product to the stage users recommend it to friends.

Applying the pirate funnel to eBaymag product metrics

Building the Growth Hacking team

Most growth hackers consider that in reaching quantum growth, you need to be involved in all activities related to your product, from design to development. That’s why Sean Ellis identifies up to six roles for the Growth team in his Hacker Growth book, including growth leader, product manager, software engineer, marketing specialist, data analyst, and product designer.

Far from every business can afford six employees to cover all the roles. Typically, startups attempt to unify all these roles in one position—Growth manager or Growth strategist. These Swiss-army-knives specialists are quite rare on the market, but businesses are not giving up on finding them. Just start a LinkedIn open job search to find thousands of requests for them.

The Martian hint to solve the problem is simple—start with just one Growth leader who spends 100% of the time focusing on growth tasks. This role requires “spreading the growth virus” to the entire product team, building the hypothesis verification workflow, and training a team to carry out experiments.

But the primary and the most crucial responsibility is to team up representatives from marketing, design, engineering, and business analytics to exchange information to build a universal understanding of what’s going on and contribute specific ideas to the growth. Practically, in this case, you have 5-10 people from different departments in the Growth team.

The eBaymag Growth team now includes specialists from eBay and Evil Martians: from support, marketing, design, frontend, and backend teams. They spend just a certain amount of working hours on Growth Hacking—and not more than 50% (typically much fewer). Every contribution matters even if it lasts less than a minute—sometimes, a bare idea or detailed answer about the inner processes is enough to create a new direction for experimentation.

A couple of words about the marketing specialist role: the reason Growth Hacking is widespread now is in unjustified marketing expenses. However, the marketing specialist is one of the most critical functions as marketing is responsible for finding new sources of users. Initially, the eBay marketing team defined the audience of sellers to send a newsletter, show a banner, or offer search advertising independently. Growth Hacking has helped improve marketing metrics as well. Now campaigns have a much stronger effect, as eBay has a method to outline more accurate target audiences and the expected result. Growth Hacking answers the question of what to promote and for what audiences, while marketing decides where to do it and with what instruments, allowing us to use marketing budgets wisely.

Synchronizing with the team

We have to keep in mind that only sustainable and well-functioning products can provide steady growth over a long-term period. Thus, the team always needs to balance experimenting and maintaining product operability. Especially when a team is shrunk due to some budget or engineering reasons. How to reach it?

Once a week, in eBaymag, we synchronize with the whole engineering team to prioritize maintaining and new hypothesis requests. For instance, if we have to migrate service from one server to another, we need to pause experiments as the migration requires well-coordinated work of all engineers. In this case, even the key player—the Growth Leader (who is a backend engineer) returns to his main specialization.

During our weekly calls, every team member sets aside some time to Growth Hacking for us to schedule the available resources for a week ahead and design a scope of work. The Growth team members symbiotically explore growth options and trends to create hypotheses, evaluate and prototype the ideas, and measure the result: fail or scale.

Besides, at least once a month, we have brainstorm sessions for generating ideas where all the team focuses on a specific area for growth.

Documenting the process

Documenting in Growth Hacking is a whole new area that deserves a separate article on the topic. Please let us know if you want something of this kind. But the main points are the following.

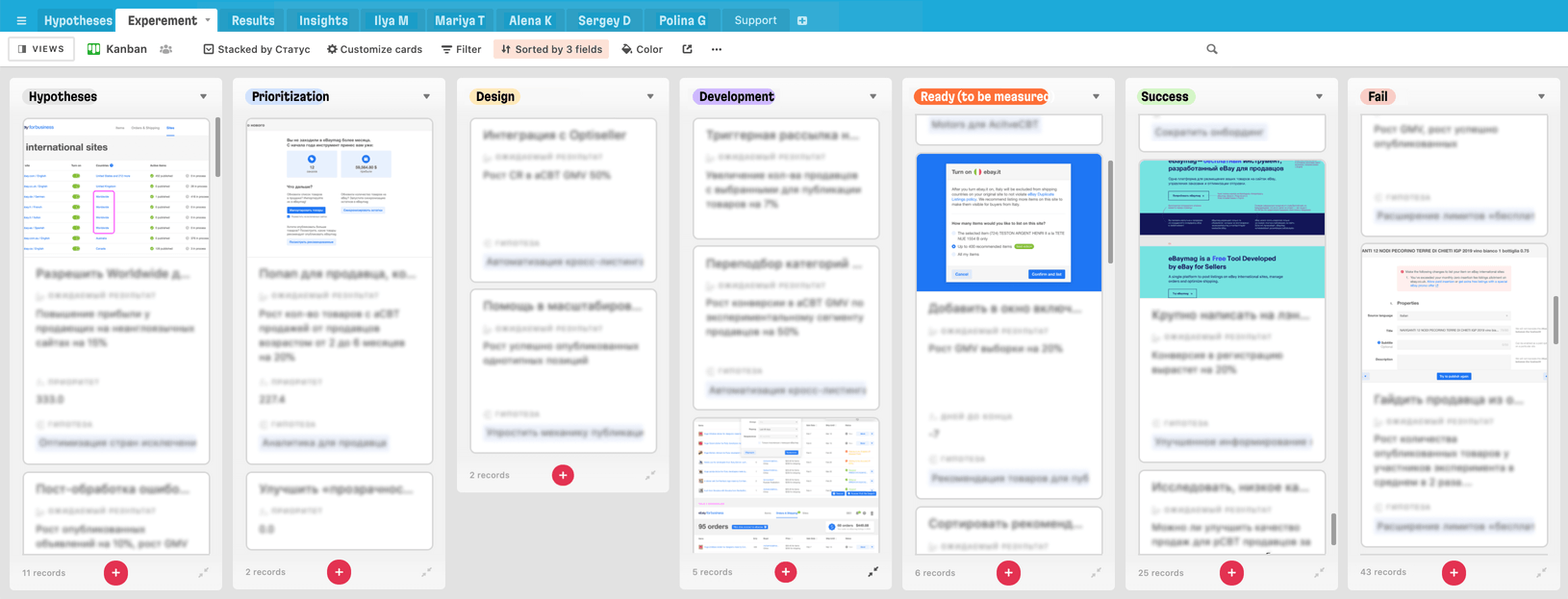

- We maintain all the project planning assets in Airtable. Anytime, each of the team members can put there any hypothesis on improving one or some metrics in this format: “IF we remove that button there, THEN our conversion rate will increase by N%.”

- During weekly calls, the team evaluates the collected ideas with the ICE prioritization technique (Impact, Confidence, Ease).

- Winning ideas are checked in a series of short experiments.

- Then, we use a simple Kanban board in the same Airtable account for experiments according to a cycle: hypotheses → prioritization → design → development → data collection. After that, they go either to the fail or the success column. The last ones start a new cycle to be released.

- For each experiment, we record all the details: Fail and Scale results (where they were and what did they influence) and insights (what did we learn).

eBaymag Growth board in Airtable

Coding and erasing

The most dangerous myth about Growth Hacking is that it leads to poor technical solutions. Indeed, it’s a common situation when rough-and-ready experiments kick in overnight. But the Growth team is immediately busy with new experiments, leaving a raw feature on production as it is because there are no resources to put the finishing touches. As a result, we have Frankenstein service made from poor code and inconsistent design instead of a genuine product.

The reason is in all these races in chase of metrics’ growth. The situation makes Growth teams limit the time resources (like only up to 6 hours per idea to investigate), so scaling processes for successful experiments remain poorly adjusted. What to do?

The Martian Growth team never sacrifices the quality of code while experimenting. In case of failure, we immediately clean up the codebase. And in case of success, we already have a piece of good code to scale. Also, we can take the liberty of having less time for experiments. We have one week (at best) for each hypothesis and don’t spend too much time on testing until the experimental feature grows to its scaling stage. Again, the feature has detailed documentation only after a successful experiment proved it.

It’s pointless to give any common hints on the best engineering practice for successful experiments as development processes, human resources, and environments are specific for every project. But if you don’t want to birth a monster, sound common sense is enough.

- Do not generalize and obey experimentation rules you read somewhere.

- Find optimal time for the experiment arrangements suitable for your team, where the code lines you add don’t increase the “engineering debt.”

- Use tools to isolate experiments like feature toggling.

- If possible, do the manual experiment without changing the codebase (e.g., try to replicate a user’s actions in the interface) to test your hypothesis.

- If you cannot do it without coding, then follow the code standards and monitoring automation you use for your typical development tasks to avoid any deterioration.

What comes next?

If you are dead set on extending this approach for your project too, here we recommend some more vital steps to do:

- Find your own North Star and make it your checkpoint.

- Set up and constantly monitor analytics according to the “pirate funnel” method to understand the bottlenecks and keep an eye on the effect of the experiments.

- Assign the Growth Leader role to one of your teammates. It’s more than enough to kickstart a process of hypothesis generation.

- Organize the documentation process and storage of artifacts—experiment results and insights. Please do remember that an unrecorded experiment cannot bring any value (according to “Pics or it didn’t happen” Instagram rule).

- Find balance acquiring new knowledge and necessary product enhancements to move business metrics off the ground.

- Arrange further management to incorporate Growth Hacking tasks into your product development process.

- If your growth processes are intensive and you already have some promising business results, it’s time to extend your 100%-focused Growth Hacking team with a new member (like it happened to the eBaymag team). You might want to assign this new person a role to organize the whole process from experiments sketching to product feature implementation, or specific accountability to carry out experiments. However, one of the key features of Growth Hacking is the roles juggling that allows reallocating resources, taking the best from every employee involved.

Also, you can check out Martians leveraging Lean software development to ease product’s growing pains in this post:

Once you drift into Growth Hacking waters, you will immediately find the following questions rhetorical. Why should you waste your time designing a full-functioning feature if you can test an effect on its prototype? Why spend a budget on a multi-page web portal if you can check a user demand for a product on a simple landing page? Why throw away a fortune on advertising that targets an off-target audience? And the last, the most critical question: why create anything without measuring product metrics and plan the next steps without results of the previous ones?

Growth Hacking can successfully empower not only corporations but small startups at their early stage. You have all the resources to build this process on your own and budget-friendly. To start, assign one person with a 100% focus on growth tasks and determine a product’s basic metrics as Martians did.

If you want to give a try on Growth Hacking for your product but lack time or experience resources or need a guide, Martians will be happy to give a hand both with the methodology and engineering for successful experiments. Please feel free to contact us then or take a look at customers we already helped.