Lean by design: 5 wins for one product

See how we turned the tables on product development process at eBaymag.com when the project was challenged to scale. Learn how putting a designer in charge and borrowing from Lean software development handbook can help ease product’s growing pains.

For the past two years, we have been working with eBay on eBaymag.com, a startup that helps sellers outside the US scale their businesses across borders. While we were still in the MVP phase, running product development was a breeze. Sticking to Agile Manifesto kept us covered: we prepared designs, built features and released them in quick iterations while collecting customer feedback through our call center.

We managed our work in a simple and straightforward way that might sound familiar: a product owner (our client) together with our team lead rearranged the backlog weekly and engineers picked their tasks from the top of the list. Our UX designer turned specifications prepared by engineers into layouts.

It worked marvelously until it did not. Once the project started to mature, we realized that the “bare-bones” approach did not cut it anymore.

The project, experimental at the start, got into a bigger spotlight. With more features, more users, more stakeholders, and more requests for changes, defining priorities became less straightforward. With a lot of interconnected issues to pick from, settling on a single problem to tackle next turned into a challenge.

While the scope of the project kept growing, it also became harder to run everything directly by our client. It became clear that it was time to set up a better process.

eBaymag.com helps eBay sellers scale their cross-border sales by listing their items on multiple sites at the same time

The designer takes the lead

One solution would have been to hire a dedicated product manager—a “business” person who could stand between the team and the product owner. Instead, we chose something that we already tried at Evil Martians before: promoting a UX designer to a Product Designer position.

It was not about putting more responsibilities on a busy team member so we could tick some internal management boxes.

For our designer, a new managing role made complete sense: while developing an interface, a UX specialist already employs a “user first” approach, and taking the lead makes design “proactive” (here’s what we should develop) instead of “reactive” (here’s how we should make engineers’ work look like). On top of it, a person we picked for a task already had a skill-set and experience required for leadership.

With all the team’s resources at her disposal, our product designer became in charge of outlining the roadmap for the whole team, setting the priorities for developers and employing analytical tools to gather feedback so we can either confirm a feature’s success or take a lesson from something that failed to deliver results.

This approach, in fact, borrows from Lean software development handbook that stresses the importance of empowering the team, seeing the product as a whole, and amplifying learning, as described in The Lean Startup by Eric Ries.

Finding a team flow that worked for everyone took us six months of gradual adjustment by trial and error. In the end, we distilled five points that we are ready to share with anyone who is looking for a better way to run a product.

1. One team*

With a designer now in charge of the product, we rethought the way we communicate. We developed a common agenda for an “extended” team that includes engineering, design, support, marketing and business people. Our product’s value proposition, its target audience, core hypotheses, planning horizons, and current strategy are now discussed openly in meetings that include everyone mentioned above plus our client, the product owner.

One way to structure those discussions is to use Lean Canvas—a “one-page business plan” model that takes under 20 minutes to create. Discussing product’s present and its future in the open, with all stakeholders involved, orients each team member toward common business goals. The trick here is to make sure that team culture permits asking hard questions and voicing concerns.

In our experience, no time spent on business discussions with engineers is wasted, as it translates into better prioritization and allows engineers to make better everyday decisions.

We also learned that never losing sight of bigger business context proves to be motivating for the team, as the business never gets boring.

2. One language

It is too easy to make a product owner believe that engineers only want to try out shiny new tech and play with fancy algorithms while designers are only interested in experimenting with “cool” fonts and neat interfaces of their liking. When that happens, product owner loses trust in the team and is forced to micro-manage: approve every minor detail of mock-ups and personally track engineers’ progress.

Establishing a product-oriented process means re-establishing trust between those who define problems, those who find solutions and those who implement them.

To rebuild that trust, a product designer needs to talk to the client about business expectations, not details of the implementation. That means learning some business speak, so no vital information is lost in translation. The way to do it is to read the same documents and reports as the product owner and discuss priorities in the same terms.

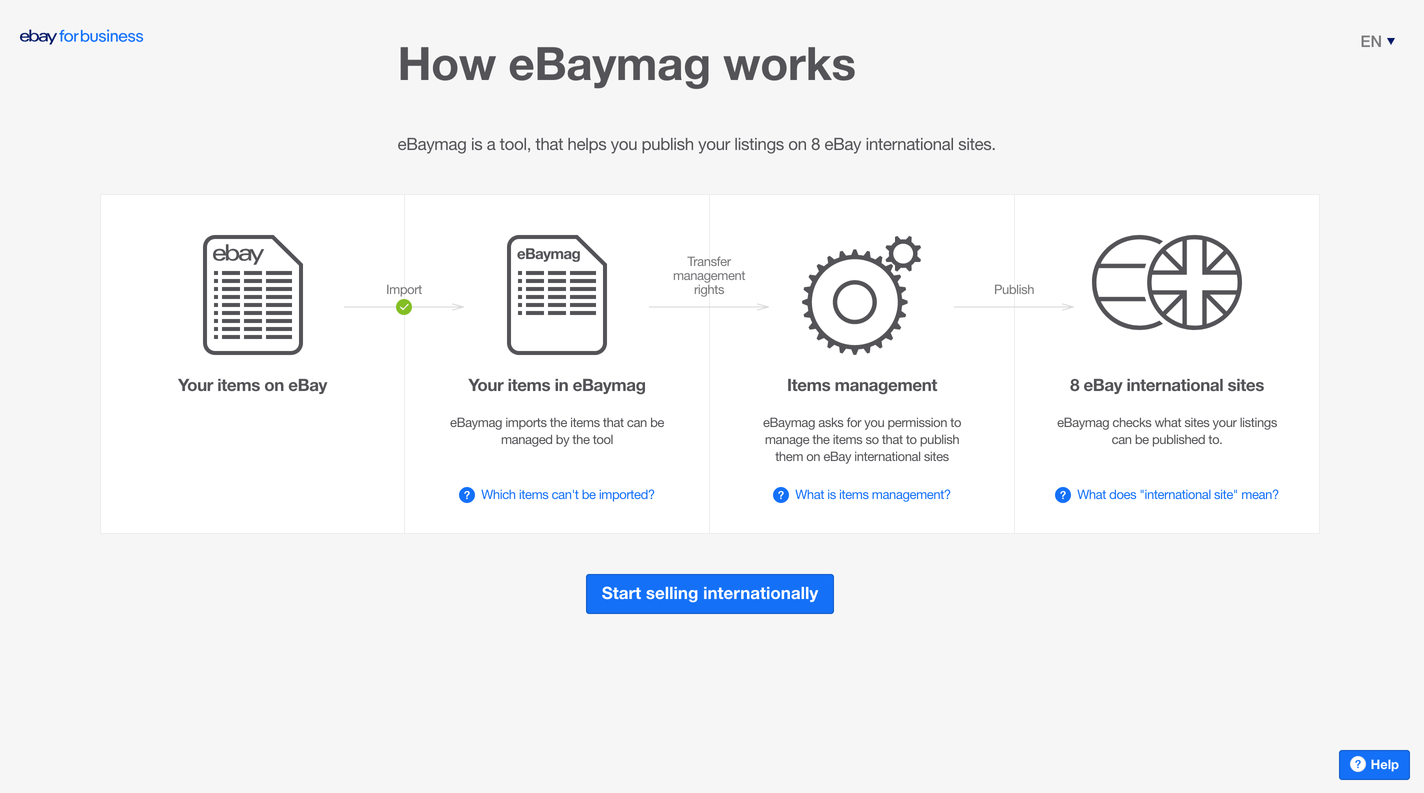

The onboarding tool was one of the first features we released under a new process. It allows new user to get initial value from a product right away

3. One roadmap

We stopped taking tasks directly from the backlog. The only person who deals with it now is the product designer who only uses an exhaustive list of tasks as a source of inspiration for a roadmap.

A roadmap is a document that allows an entire team to keep an eye on upcoming product releases. It is the primary communication tool for the extended team and all stakeholders. Product managing designer is the one who builds it and owns it.

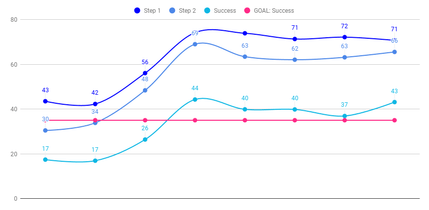

A roadmap can be seen as a literal map: a way through the woods towards the shiny goal. A treasure hunt. Of course, you need to define “treasure” first: be it an increased number of active users, their projected earnings, or anything that makes sense for your business.

Once the goal is set, a product designer breaks the path down into specific steps. While doing so, she sets up a well-defined measure of success for each step. For instance, “this release will double this particular conversion, as measured two weeks after going live”. That also makes development more predictable: turns out, we are more often correct in our forecasts than not.

Feature performance tracking using Google Analytics add-on for Google Sheets

The roadmap is not set in stone—as new obstacles arise, the path changes, so it is essential to keep everyone updated: our designer does it during a weekly call with the extended team. A weekly “roadmap screening” keeps the whole team focused and clear on our nearest goals and our progress.

Once the team is done with research, decomposition, and estimation for a particular release, we can put a planned release date on a map. It is important not to start with a date already in mind! Initially, our releases don’t have any estimates, and we avoid promises to deliver on a particular day.

In our experience, early estimates can never be trusted—they only lead to irritation and stress.

It is also important to revise and update estimates as the project progresses—we do it at least once a week.

We use Jira Epics to describe steps: a board containing epics serves as a visual representation of the roadmap. Each epic, which represents one upcoming release, is decomposed into technical tasks and is linked to designs, testing scenarios, and release notes.

Last but not least, we do not put minor technical releases on the roadmap—only those things that we believe will affect metrics significantly.

4. One owner of analytics

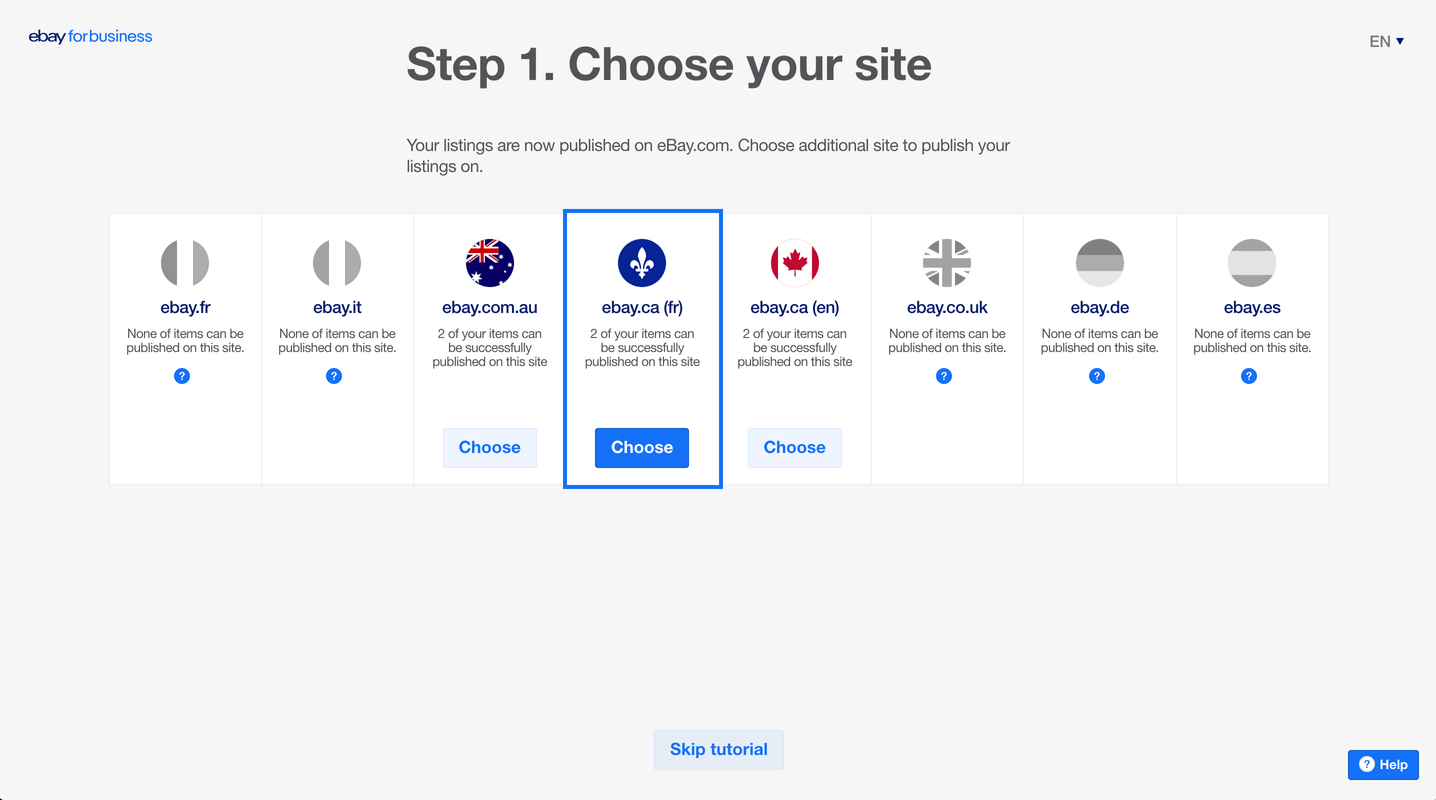

Our product designer has become the owner of all product analytics. The client also has a list of metrics to track, but those are more high-level, such as monthly active users or revenue growth. A designer, however, needs a set of tools to predict immediate user behavior and validate those predictions quickly.

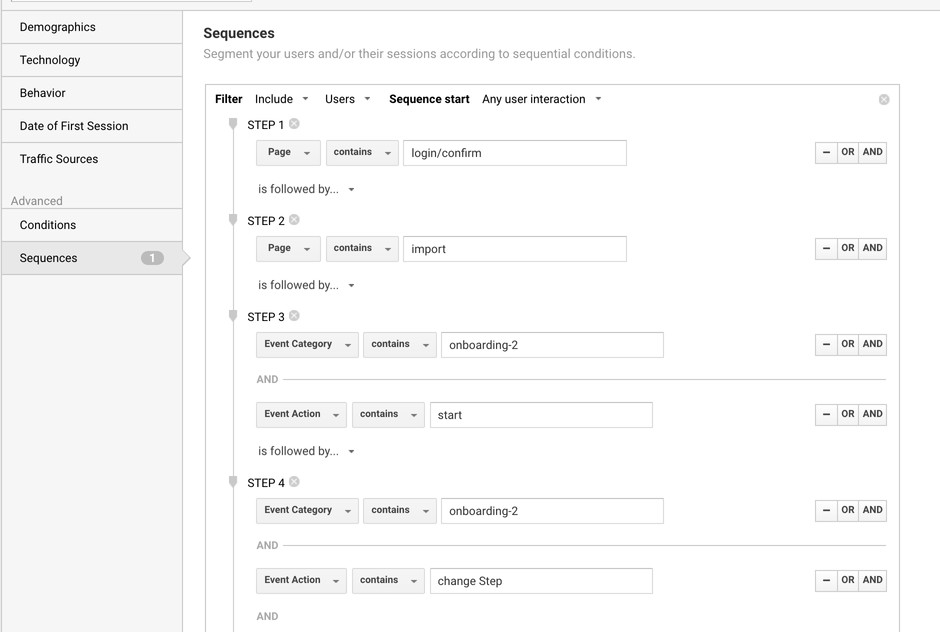

In order to make an educated guess about the feature’s effect (“a clear onboarding flow should increase the share of active users by N per cent”), a product designer needs to come up with a list of questions: what audience do we want to target with this feature? How many users fall into this category? Who are the others? After all the necessary data is collected and processed and the hypothesis is formulated, our designer comes up with a set of metrics she wants to be tracked after the feature is implemented: for instance, how many users proceed to the next step of the onboarding. We usually combine different sources of data, like monitoring reports from the backend and sequences from Google Analytics.

Custom segments in Google Analytics help us track custom funnel performance

Measuring feature’s success also requires talking to users directly. Our product designer collects feedback from customer support, comes up with question sheets for surveys and schedules regular video conference calls with people who use our product daily.

5. One cycle

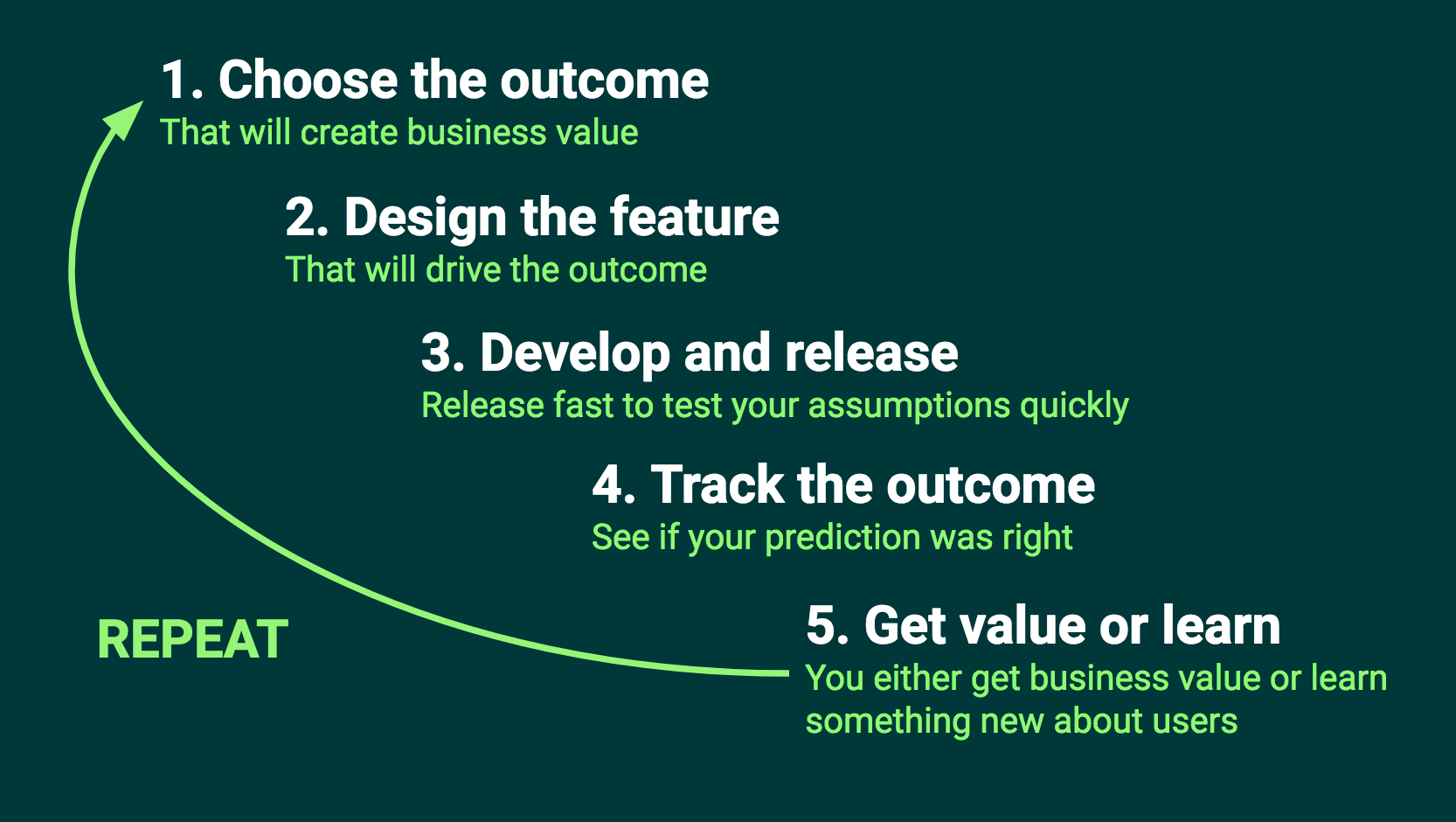

Here’s what our new product development process looks like after the product owner gave us a new business goal (for instance, reach a certain amount of monthly active users):

Lean product development process as led by a product designer

- A product designer creates a path towards the goal as a roadmap with checkpoints. Each checkpoint has a predicted outcome that brings us closer to the business goal.

- With that outcome in mind, the designer describes the feature that engineers develop and release, she also provides a set of requirements for analytics.

- After the release, we track our metrics to see if we got to the checkpoint and the predicted outcome is achieved. More often than not, it is achieved.

- If we did not get what we expected, a product designer digs into analytics and user research to learn why the hypothesis did not work.

- The cycle is repeated.

The gain

What started with a single responsibility shift led to a whole product process being re-shaped. Our current tasks, immediate plans and midterm goals are clearly defined. The product owner can concentrate on high-level tasks and business strategy.

The whole team has become more productive and feels continuously rewarded as we move in small steps and celebrate our victories often.

Satisfied with our little experiment, we recently added a second product designer into the mix, and our new dynamic duo has already managed to reach ambitious goals for three consecutive releases, keeping the team motivated and happy.

Thank you for reading, and feel free to mention us on Twitter if you have anything to add, perhaps, a detail from your experience? Or contact us directly if you wish to talk privately.