Super speed, super quality: lessons from the Aptos Network site launch

Evil Martians have proudly collaborated with our client Aptos for 3+ years. Recently they had a special task: a brand new website in just one month! In this post, the secret Martian sauce that allowed us to win a race against time, lessons learned on the way, and practical advice for achieving development goals without compromising quality!

The Aptos Network homepage!

For context, due to the necessity of time, this task involved a lot of U-turns, clever tactics, and compromise. But our hard work paid off when the whole thing came together …just in time for the client’s ultimate satisfaction!

Proactively collaborate with designers and build a design system

The deadline was fixed, so a lot of design work had to be done in parallel with development. (The final version of the site’s pages was received around one week before launch.)

That said, even more important than seeing all the pages upfront? Seeing the building blocks used to construct these pages (plus the primitive components that make up these blocks). And that’s exactly what we had to work with!

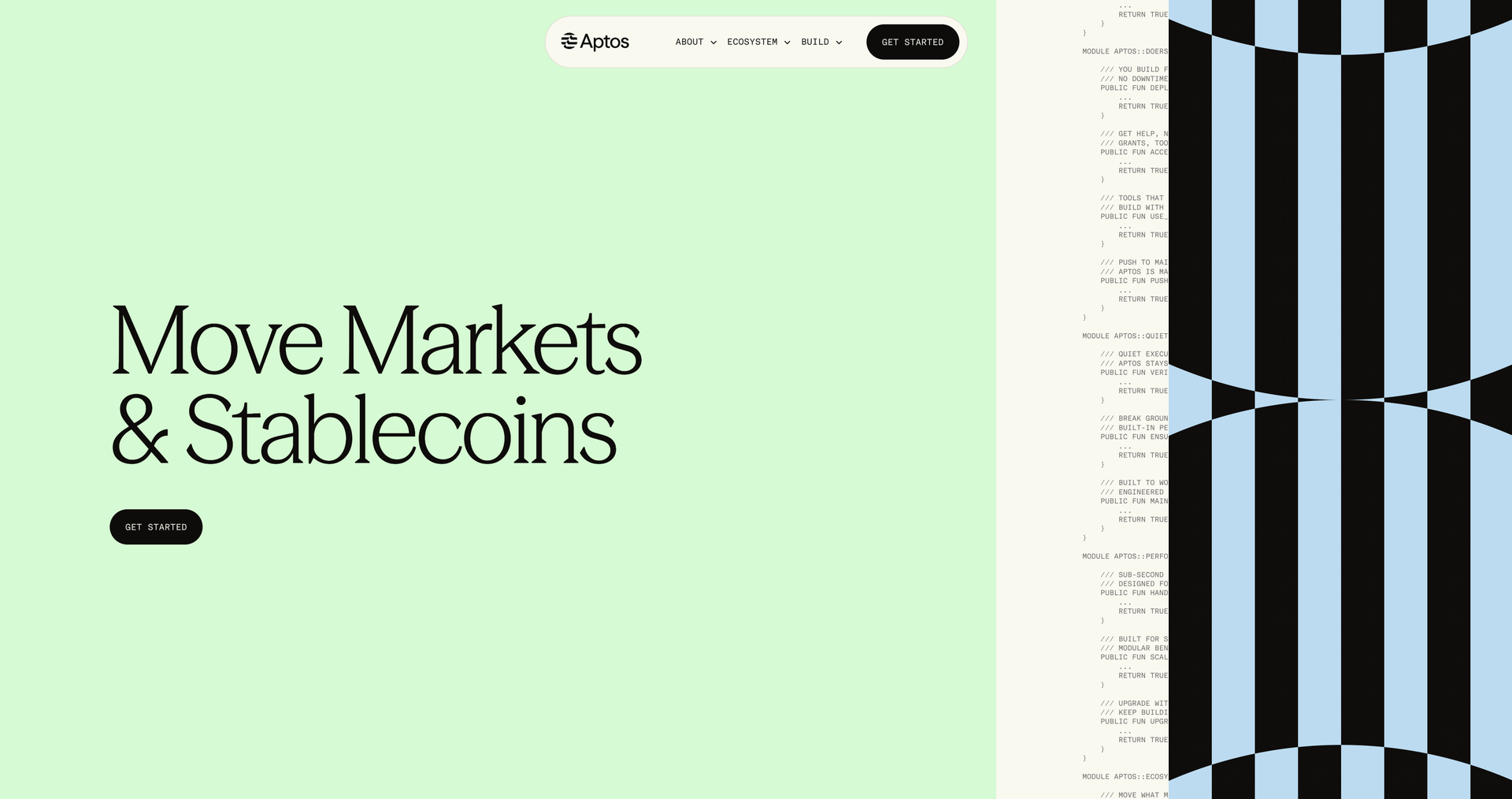

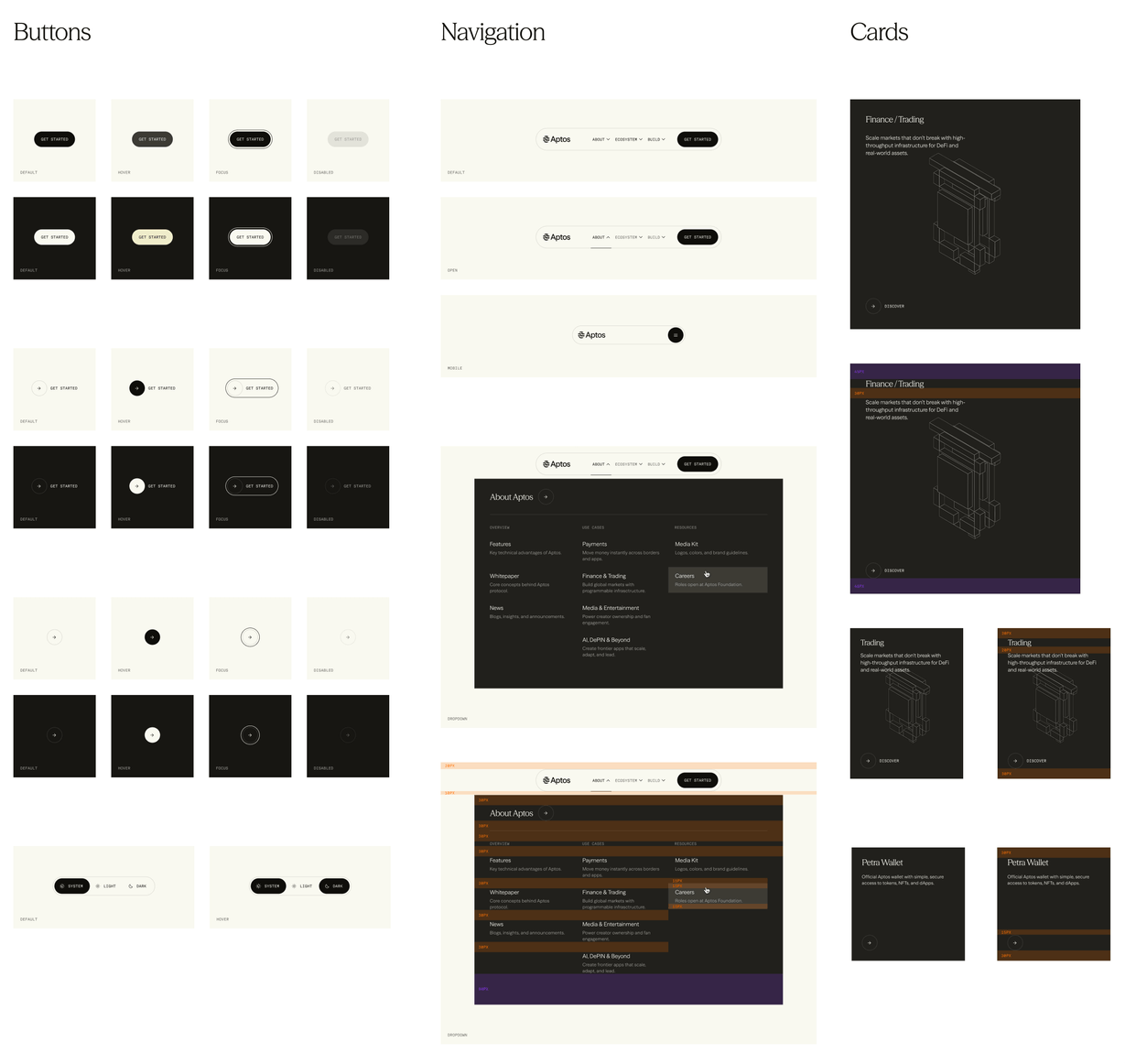

Aptos Network design system components

Having a locked-in, component-based design system was the first cornerstone that allowed us to move fast and implement section after section, focusing on the business logic and unique features. (For everything else, we just reached into our pre-built custom toolkit):

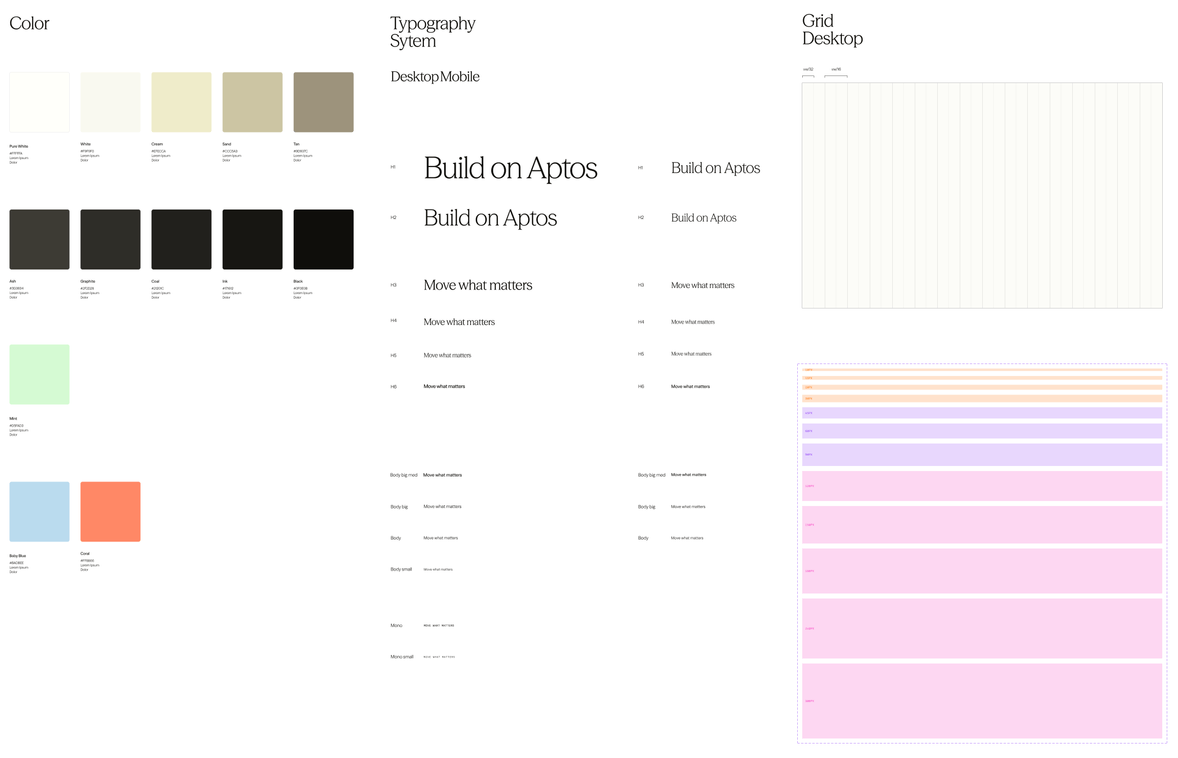

- Typography. A pre-defined set of fonts, sizes, weights; everything tokenized and wrapped in a

Typographycomponent. - Buttons / Links. A unified, carefully composed interface for anything that is clickable, capturing the very essence of brand identity.

- Colors. A limited tokenized set of colors and their theming behaviors: does this color have a dark mode alternative? Does it locally rotate the theme when there’s text on top of it?

- Sizing / Spacing. The Aptos Network design concept had a lot of elements dynamically sized by an invisible grid. But everything else that has some fixed size, should be defined by a token.

Primitive tokens are the first step to Design System Victory

The list goes on, but you get the idea: collaborate with your designers and build what best suits the project’s needs! Talking, listening, providing feedback, and discussing solutions is where development speed is born, long before we touch the keyboard.

Negotiate the requirements and priorities

Indeed, real speed doesn’t just come from typing faster. As we go further into the AI era, I increasingly hear a common misconception that “you can be a 10x developer if you produce 10x code”. That’s not entirely true. To put it more precisely: you become a developer that produces 10x technical debt, not necessarily 10x value.

Value grows as feature definition gets narrowed down

I like Juraj Masar’s take on this subject. In his article, he talks about how the real potential of making an engineer 100x is in questioning feature definitions. This aligns well with the way we operate here on Mars, as it allows us to bring our clients the most value.

Hire Evil Martians

Evil Martians make the impossible possible: reach out, launch faster, and let's go!

So, when we were first presented with the timeline for Aptos Network we asked: where can we narrow the scope? What’s your definition of MVP? What is an absolute must for the initial launch and what isn’t?

As our friends from Ashfall handed over designs, we tried to narrow the scope.

But, actually, reducing the page count wasn’t an option due to the nature of the project.

You see, the new website was technically a reincarnation of the previous website (aptosfoundation.org which currently redirects to the new domain). This meant that all the existing links were also expected to keep working (e.g. if there was a page at aptosfoundation.org/builders there must be an equivalent page at aptosnetwork.com/builders).

All pre-existing pages had to migrate to the new website

So, we couldn’t reduce complexity by pushing some pages back to post-launch. That made the situation even trickier. But, a-ha! Turned out there were some features that could happily wait until after first version, without compromising the usability of the site and its ability to make a good first impression on the community.

Those features included:

#1: Full CMS integration. The cornerstone of our timeline optimization. Initially, all pages would build dynamically, driven by a headless CMS. While we were excited to bring this idea to life, it became clear that the proper setup required for that approach didn’t fit into the timeframe.

Of course, some data-collection pages like Blog or Ecosystem Directory had to be driven by CMS no matter what (the marketing team needed to be able to create those records independently). Moreover, they already had a ton of records on the old site that had to be migrated to the new one.

However, most of the other pages could live being filled with locally defined data. That’s what we did, while, of course, abstracting the data as if it was coming from an external source to facilitate future migration to the fully CMS-based approach.

#2: Animations. Ashfall’s beautiful brand work included some tricky animations; these are currently live on the site, but we actually ended up implementing them in a future version. This was a good call, as animations like this requires a lot more attention than we could spare that at the time.

#3: Search for ecosystem directory. While an important feature from a UX standpoint, it was not a critical feature for the first version. This made it a good candidate to postpone.

No matter what, estimate

Since we were working in parallel with the designers, it could be hard to precisely judge how we were doing on time or any speed adjustments we’d need. This situation is quite common in dev world, but if not treated properly, it can result in development cycles stretching out indefinitely—something we could not afford with the deadline as tight as ours. But still, don’t wait for task definition to become complete: sit down and estimate.

Forcing ourselves to estimate helped us discover some pages missing from the initial scope, but which had to be present on the final website due to regulations. That early discovery totally saved the day—finding this closer to the deadline would not have ended well.

Even more importantly, this allowed us to realistically look at our schedule, understand that the time that we have left may not be enough to deal with what’s currently on the table, and raise the flag before it was too late.

Which brings us to the next point…

Know when to attract more people

We started this project with just the two of us, Pasha and me. We kicked off pretty smoothly, transferring some utilities that we knew would come handy from past projects, taking care of the architectural decisions, laying ground for the design system.

But very soon, we realized that our current pace wasn’t going to cut it. The problem: we were already working at the top of our capacity. Thus, the team configuration itself had to be adjusted.

This decision didn’t come easy because we knew that team size to created value proportion is not linear. In other words, putting 3 engineers on the task doesn’t mean the task is going to get solved 3 times faster. Yes, there’s more work being done, but at the same time, there’s more work to review, more time to spend discussing decisions, syncing context, and planning.

Still, the situation called for decisive action. Even if team expansion resulted in a smaller, non-linear speed boost, that would still make a difference, so we went for it.

In the end, it was totally worth it! Kudos to fellow Martian Ivan Eltsov for doing great work onboarding the project in no time and helping us create a bunch of components. What made this possible was the fact that the design was so modular, and we could easily separate it into isolated groups of work.

Choose the stack wisely

Here’s what we ended up building with:

- Astro. Nothing beats Astro for SSR/SSG setups. Pick any UI framework or none if you’d rather go vanilla. Go from SSG to SSR with a single line. Choose from a rich list of adapters to deploy virtually anywhere you want. Control precisely what gets hydrated on the client and what doesn’t. (Ok ok, I’ll stop myself before this post turns into another Astro love song.)

- Tailwind. Now, I’m not the biggest fan of Tailwind, but one thing that it really shines at is creating these tokenized design systems and almost forcing you to use them. Having chosen it as a CSS framework also gave us a speed boost, similarly to how TypeScript speeds you up in the long run, even though on the first look it seems like a more complicated version of JS. Although we would still resort to good ol’ vanilla CSS when we needed to do some real style heavy-lifting.

- React. This one is interesting, because no one on the team wanted React, but we ended up riding it anyway. How come? Keep reading to find out.

Make the batteries replaceable

In other words, handle the dependencies strategically to avoid coupling as much as possible.

In uncertain contexts, you often need a plan B. Post-factum, it’s easy to say “We should have chosen TOOL_NAME from the start”, but at the beginning it’s not that simple at all. You just don’t know what surprises lie ahead.

So when you’re planning, especially when you know the timeline is going to be tough, make sure to set up your architecture in a way that would support replacing parts without disassembling the whole thing.

Example: abstraction layer for the hosting provider

Astro (being as awesome as it is) has a list of adapters, that act as an interface between the framework and host-specific APIs. This in itself already is a solid abstraction layer that makes the cloud provider replaceable. Just switch to a different adapter and you’re good to go.

But more often than not, projects grow to have more ties with the hosting environment (ours sure did). That includes runtime checks, cache control etc. Now that already isn’t as easy to transfer, should you decide to move to a different hosting provider.

The solution is to have your own “adapter”—an abstraction layer for all hosting APIs that you rely on.

The simplest demonstration would be: instead of this…

import.meta.env.VERCEL

? "Running in deployment environment"

: "Running locally"Do this:

import runtimeApi from "~/lib/runtime"

runtimeApi.env.IS_DEPLOYMENT

? "Running in deployment environment"

: "Running locally"

// ~/lib/runtime

import { vercelApi } from "./vercel"

import { netlifyApi } from "./netlify"

export default vercelApi

// ~/lib/runtime/vercel

export const vercelAPi = {

env: {

IS_DEPLOYMENT: import.meta.env.VERCEL

}

}This avoids hard coupling your code to a specific vendor, and gives you a focused API that you can re-implement, should the need arise to switch providers.

The same concept applies to any large crucial dependencies used across your code. Make APIs you control, implement the factual dependency there. This makes your life easier in the long run and lets you iterate faster.

Example: safety net for critical dependencies

When we were choosing a UI framework we ran a benchmark test for all the frameworks we were considering (SolidJS, Svelte, React and Preact). We implemented the same component four times and looked at how different frameworks affect bundle size and loading times. React expectedly showed the worst result of all. Preact and SolidJS were very close.

We really wanted to pick SolidJS, but eventually decided to take a calculated risk and choose Preact. The main reason wasn’t just performance or bundle size—it was the fact that Preact offers a React compatibility mode. That meant we could keep access to the React ecosystem and, more importantly, have a clear fallback plan in case things went wrong. Given the tight deadline, this safety net mattered.

Good thing we did! Unfortunately, our experience with Preact compat on this project was not the best. Very soon random problems started arising—some components didn’t work as expected at all with Astro islands, apparently failing to keep the context.

But at the time we realized the seriousness of the problem, we already had a bunch of components relying on Preact APIs. And at that point we really didn’t have spare time for a rewrite.

So what’s the solution? Once again, replacing the batteries! We uninstalled Preact, installed React in its place, and kept going. The real trick was to leverage Preact’s compat layer and write imports like this: import {...} from "react", aliasing React to Preact. This approach allowed us to migrate from one framework to the other while not wasting valuable time on global refactoring since the deadline was just around the corner and we needed to make fast decisions.

Reuse experience from past projects

Like I mentioned earlier, the new website was technically a rewrite of the website that went before that. While everything from visuals to the framework powering it was different, some blocks of logic and utility scripts—remained.

Having this layer of functions disconnected from the factual implementation made it easy to bring it over to the new project and start using them there.

I encourage you to try it! You can start adopting this structure today:

utils/Here go the most abstract bits that have nothing to do with the business logic or the specific framework you’re using, e.g.utils/arrayorutils/assertions,utils/cache. These ones you can bring over from project to project, even if they have nothing in common.lib/Here we put the reusable utils related to the domain. These you’ll be able to reuse if you need to re-implement the project for whatever reason.components/That’s where our usual components go. See? Untied from logic.

AI

Since we’re talking about speed here, I bet you expected to find this section closer to the top. But the reality is, most of the work on Aptos Network was done without AI.

Of course, we leveraged AI here and there, for some simple isolated tasks, code completions, research, tests, one-off scripts. But still that was much less than you might’ve imagined.

Why? First and foremost, AI can have an effect quite contrary to what you’d expect. Meaning, it can actually slow you down. In fact, there’s a study, that shows that developers believe AI is speeding them up even when it’s actually slowing them down. Counterintuitive, I know. Aren’t all our social media feeds filled with posts about how coding agents speed everybody up? Well, yes, but it comes down to a couple of important factors:

- How maintainable are the results and do the authors even care about maintainability? This isn’t a sarcastic question. There are apps (and I do believe they’re a perfect use case for AI), where you know from the start that you won’t need a v2. Such disposable software we can vibe-code away, be messy, and say “it’s good as long as it does the job”. The codebase will never need to be looked at by a human anyway. This was not the case at all with Aptos Network. We needed a fast initial release, yes, but just as importantly, we needed a fast iteration cycle. And that meant we needed to make good architectural decisions from early on.

- How common is the task? Does AI have the capability to solve it? Aptos had a very specific idea for this project: a CMS-driven site with a highly modular design. You can imagine there were a lot of moving parts to set ground for: querying data, handling ISR, caching, revalidation. AI is pretty good at solving common tasks, but not the ones where there isn’t a ton of pre-existing research, the ones where you need to actually use your creativity.

- Coding with AI is an experiment. “AI can help me with this task” is not the absolute truth, it’s an idea to validate. You can never be sure in advance the result will be what you need it to be. Sometimes it turns out fine. Sometimes it doesn’t. In the second case you’re risking to spend a lot of time prompting, and then still be left with a not working solution in the end. That means spending double time on the task than if you went ahead on your own in the first place. Try prompting a couple of times, and if you see it isn’t working, switch back to manual coding to avoid wasting more time than you have to.

In other words, use code-gen AI for:

- Simple tasks, that you already know how to solve, but writing a prompt is faster than writing code.

- Isolated focused modules that are straightforward to review and correct.

- Components with clear input → output models, where the correctness of execution is obvious.

Don’t use code-gen AI for:

- Heavily interconnected compositional modules. LLMs are not great at architectural decisions.

- Component structures (many changes done at once).

- Things that you’re not sure yet how they should be implemented. You’ll just waste time on fighting AI, and then eventually still have to do your own research and manual work. In such cases it can be helpful to begin with using AI for research.

The result

Now that all of the above was done and the dust settled, our happy clients were left with a shiny new website: aptosnetwork.com.

Launched just in time. Beautiful. Accessible. Perfectly functional.

But this was only the beginning! We still had a lot to iterate on and implement all the features we strategically pushed to post-MVP. Stay tuned for more exciting technical findings and case studies inspired by our work on Aptos Network and other projects!