Tutorialkit.rb: the ruby.wasm journey goes onward

Ruby and WebAssembly are both powerful technologies, but together they unlock vast new possibilities. Evil Martians continue pursuing our goal of making ruby.wasm beneficial to the broader Ruby community (and beyond). To that end, we’d like to introduce our new project: TutorialKit.rb.

Note: This is a Ruby Association Grant 2025 intermediate report on the TutorialKit.rb project, a toolkit for building interactive Ruby and Rails tutorials that run entirely in the browser using WebAssembly and WebContainers.

First, a little setup. We’ve been exploring the practical applications of ruby.wasm since its introduction to CRuby in 2022. Coding playgrounds, games, entire Ruby on Rails applications running in the browser. All of those were great (and fun) experiments. But calling them practical examples of running Ruby on Wasm only would be a big stretch.

In other words, they were things that elicit reactions like these: “Why on Mars do you want to compile a complex dynamic runtime into Wasm???“. Luckily, we’ve found the right application for the tool: interactive coding tutorials.

JavaScript has tutorials that run entirely in the browser and don’t require installing any additional software. But with WebAssembly, JavaScript is no longer the sole proprietor of web browser runtimes. So then, why should JS libraries and frameworks maintain a monopoly on providing the best-in-class access to learning?

That’s why we decided to focus on bringing such accessible learning experience to the world of Ruby with the help of ruby.wasm.

Open a web page, write and execute code, and just see the results! Lowering the entrance bar (or eliminating it) is vital for the adoption of frameworks and languages like Ruby.

As a pilot project, we converted the official Rails “Getting Started” guide into an interactive tutorial: rails-tutorial.evilmartians.io. This is a Ruby application, a terminal, a database, and a web server—all running locally in your browser.

The future of Rails begins in the browser

Starting with Ruby on Rails helped us identify the challenges and edge cases of creating in-browser tutorials for Ruby. Rails Tutorial paved the road for a greater project: TutorialKit.rb.

Hire Evil Martians

We've pioneered WebAssembly solutions, from browser-based Rails apps to interactive tutorials. Hire us to explore Wasm opportunities for your architecture!

TutorialKit.rb extracts and generalizes Rails Tutorial machinery into a reusable framework, enabling anyone to create interactive, zero-install Ruby tutorials. At least, that’s the plan.

In this report, we’ll share our progress, problems acknowledged and solved during the first part of our work sponsored by Ruby Association. Here’s what’s covered:

- TutorialKit.rb toolkit

- Demo: Action Policy tutorial

- Research: Gem bundling architecture

- Research: HTTP support

- Future work

The TutorialKit.rb toolkit

TutorialKit.rb started as a fork of TutorialKit, a framework for building interactive JavaScript/Node.js tutorials built by Stackblitz (the folks behind Bolt.new).

Under the hood, TutorialKit uses Web Containers (also invented by Stackblitz), a technology that allows running lightweight containers with Node.js and basic Unix support in the browser via Wasm.

Technically, TutorialKit.rb is comprised of a handful of NPM packages published under the @tutorialkit-rb scope. All of them are forks of the corresponding TutorialKit libraries, but some new ones are already coming up.

Expanding from JavaScript to Ruby

Using the JavaScript-focused project as a foundation enabled us to rapidly deliver a production-ready UI/UX instead of building it from scratch. Nevertheless, adapting it to a Ruby/Rails development environment required many enhancements:

-

Virtual FS enhancements.

TutorialKit was designed to work with projects with a flat structure; support for nested directories was limited. For Ruby projects, the file system layout is important, so proper directory support was introduced.

-

Synchronization of the terminal state with the runtime preparation status.

Ruby projects are slower to boot (loading and initializing pretty large Wasm modules, setting up a database that is often required); while the container is being prepared, we don’t want users to try interact with the terminal.

-

UI enhancements.

We had to add syntax highlighting for Ruby and YAML files as well as the corresponding file icons—tutorials must look good!

-

Wasm modules caching.

To run a tutorial, we must download and initialize a Ruby Wasm module. As we’ve already mentioned, Ruby Wasm modules are pretty heavyweight, thus, downloading them on every page load would be overkill. To improve the UX, we provide a caching mechanism (store Wasm bytes in the browser via File System APIs) that supports versioning.

In addition to patches and improvements, TutorialKit.rb also provides a pipeline for building Wasm modules that contain the Ruby runtime and all required dependencies (more on how bundling works below). The pipeline uses the wasmify-rails gem to configure and run compilation and packaging commands.

How to use TutorialKit.rb

TutorialKit.rb is ready to use today. Just run the following command (a Node.js runtime is currently required):

npx create-tutorialkit-rb my-rails-tutorialThe command above launches an interactive generator that helps you set up your first Ruby tutorial. Let us demonstrate what we’ve built with it.

Demo: Action Policy tutorial

Our work on TutorialKit.rb (as per the grant proposal) also includes creating real-world examples: tutorials for existing projects. As the first candidate, we picked Action Policy.

Want to build a tutorial for your Ruby project? Ping us! We’d be happy to collaborate on it to battle-test TutorialKit.rb.

Action Policy is a modern batteries-included authorization framework for Ruby and Rails applications. It introduces authorization policies (Ruby classes) and integration helpers for controllers and views as well as testing and debugging utilities—enough functionality to validate TutorialKit.rb features and identify DX and UX issues.

Here’s a demo playing around with the example tutorial lesson:

Go to action-policy-tutorial.fly.dev to play for yourself and learn how Action Policy works: how to create policies, enforce authorization, and what the common patterns are. (The tutorial is still under development. Stay tuned for the final release announcement!)

The source code can be found on GitHub: github.com/Bakaface/action_policy-tutorial.

Now, let’s dig into the technical challenges we had to deal with to build this thing (feel free to skip if you’re not a member of the Ruby Association Grant committee 😁).

Research: Gem bundling architecture

One of the cornerstone questions of building Ruby in-browser tutorials is how to pack all the Ruby code: the gem’s or project’s source code and dependencies. Tutorials usually require some context dependencies: Rails components (e.g., Active Record), test frameworks, and so on. How to pack them all for the browser?

TutorialKit.rb provides utilities for building a custom Ruby Wasm module from the Gemfile, with all dependencies bundled. This is the original approach we used for the Rails Tutorial, and it proved to work well. However, bundling everything into a single ~80MB Wasm binary obviously has downsides.

For TutorialKit.rb, we explored alternative gem distribution strategies inspired by other ruby.wasm-related projects:

- Tarball distribution (inspired by mastodon.wasm)—separates Ruby binary from gems.

- Runtime bundle support (inspired by runruby.dev)—full

bundlesupport in the browser.

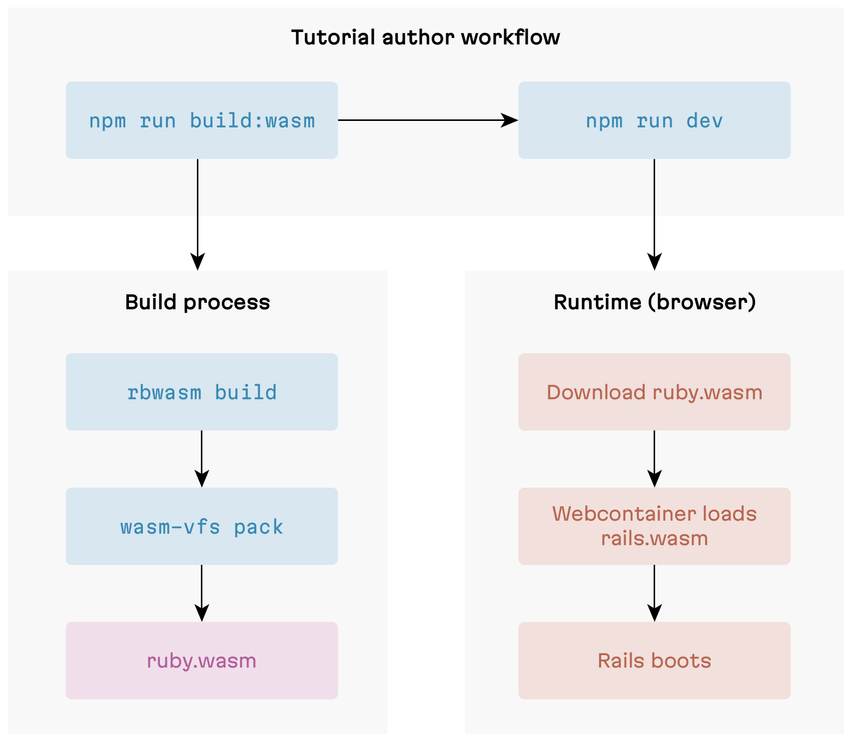

Current approach: build-time gems embedding

The current approach uses wasmify-rails’s build pipeline to compile Ruby, Rails, and all other gems into a single WebAssembly binary.

Build-time gems embedding

When you run npm run build:wasm in your tutorial project, wasmify-rails kicks off and executes the following two steps:

-

rbwasm build—Compiles the Ruby interpreter along with all gems from the Gemfile into a single WASM binary. This step downloads Ruby source, cross-compiles it to WebAssembly using WASI SDK, and bundles gem native extensions. This step takes a long time during the initial run because we have to recompile Ruby from scratch. -

wasi-vfs pack—Takes the ruby.wasm output and embeds application directories (app/, config/, lib/, db/, public/) into the WASM binary as a virtual filesystem. This creates a fully self-contained module.

When the tutorial loads in the browser, the runtime flow is straightforward:

- The browser downloads the single rails.wasm file (~80MB)

- WebContainer loads it as a WebAssembly module

- Rails boots immediately from the embedded virtual filesystem

The approach is simple: one file contains everything, and boot time is fast since there’s no extraction overhead. However, there’s a significant drawback: initial build time can take a while, adding friction to the development workflow. On our test machine (Intel Core Ultra 155H), the initial build can take up to 20 minutes. On each subsequent Gemfile update, the complete Wasm module rebuild needs to be triggered again—this will be faster thanks to caching, but still can take some time.

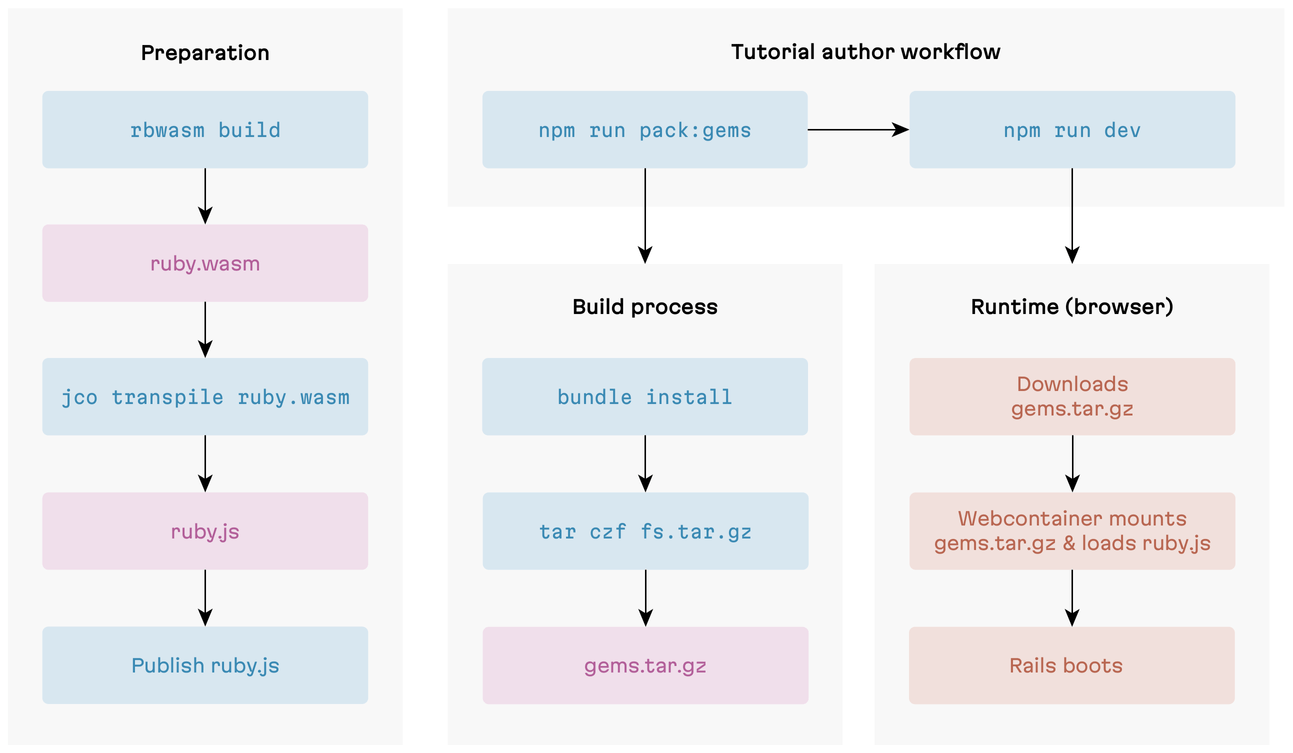

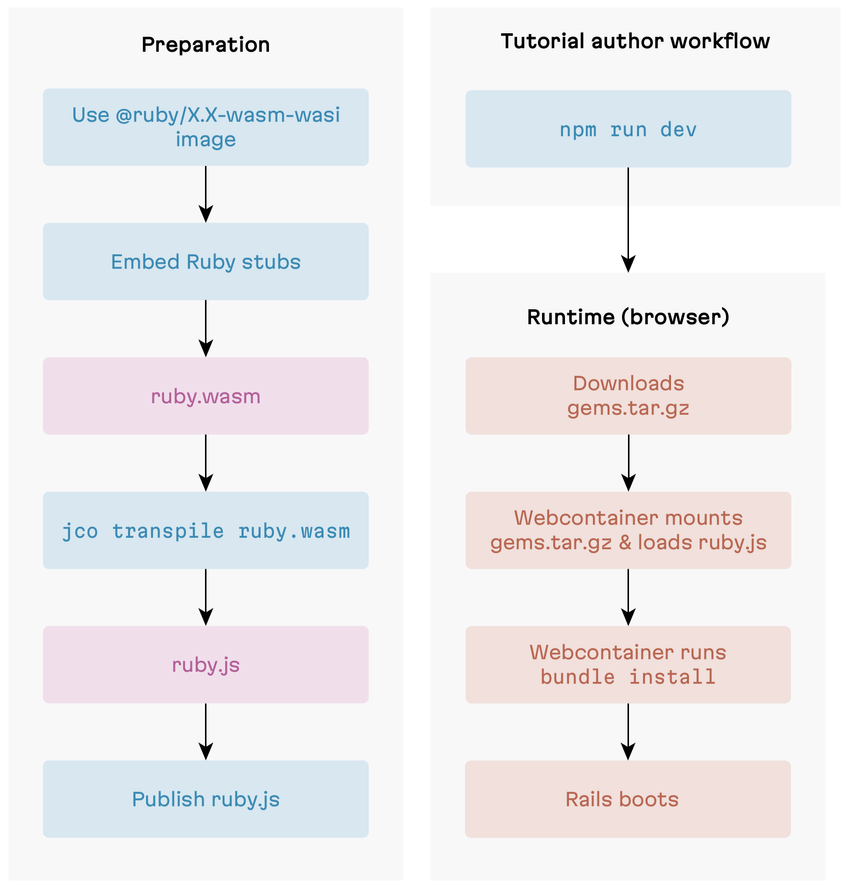

Tarball distribution

An alternative approach, inspired by mastodon.wasm by Yuta Saito, separates the Ruby interpreter from application code and gems. Instead of embedding everything into a single Wasm binary, it builds Ruby from source and packages gems into an extractable tarball.

Tarball distribution

The mastodon.wasm project uses the same rbwasm build command to build a Ruby runtime Wasm module. Why not just use the prebuilt ruby.wasm modules? Building from scratch gives full control over build flags and experimental features, such as dynamic linking. Gems are cross-compiled using Bundler with --target-rbconfig pointing to the Wasm Ruby’s configuration, and some gems use custom Wasm-compatible forks (nokogiri, nio4r, oj).

The final tarball (fs.tar.gz) contains three directories:

usr/—Ruby interpreter and standard librarybundle/—Cross-compiled gemsrails/—Application code

At runtime, the browser downloads both the transpiled Wasm component and the tarball. A Service Worker extracts the tarball to a virtual filesystem, and Ruby accesses these files through WASI preopen mappings. This adds extraction time on first load, but enables much faster rebuilds during development since we don’t have to recompile the whole Ruby interpreter.

We’re experimenting with this approach in the bakaface/tarball-gems-distribution branch.

Runtime bundle support

Another strategy, implemented by Svyatoslav Kryukov in runruby.dev, enables real bundle install in the browser by patching Bundler and RubyGems to work within WASM/WASI constraints.

Runtime bundle support

This approach is overkill for TutorialKit.rb’s purpose—tutorials have predefined gem sets that don’t need runtime installation. However, it’s worth exploring as it opens avenues for potential new applications of our Rails-on-Wasm infrastructure.

Quick comparison

| Build-time embedding | Tarball distribution | Runtime bundle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Build time | Up to 20 mins | A few seconds for packaging a tarball | None |

| Download size | ~80 MB | ~15 MB + gems tarball | ~15 + gems |

| Cold start after downloads | Instant | Additional 5-10 sec (tarball extraction) | bundle install |

| Backend required | No | No | Yes (proxy) |

Research: HTTP support

ruby.wasm has some limitations compared to regular CRuby. For example, sockets are not supported, and, thus, there is no way to perform HTTP requests. We don’t want to discriminate against HTTP-dependent projects from using TutorialKit.rb: we know that browsers can handle HTTP, so we can make HTTP accessible in TutorialKit.rb, too!

Let’s imagine we decide to create a tutorial on RubyLLM or Active Agents (yes, when we think about HTTP, we assume communicating with LLMs these days 🤖). Learning AI-related tools without access to a real LLM (i.e., by mocking requests) is not an option. We need to support calling HTTP APIs from wasmified Ruby applications. For that, we need to solve the following two problems:

- Making HTTP from Ruby without networking support

- Dealing with cross-origin request restrictions (CORS)

In theory, the first problem—Wasm networking—could be achieved with WASI 0.2 support for ruby.wasm itself. However, we’re not there yet.

An alternative approach to bringing HTTP to ruby.wasm would be to use JavaScript as a bridge between Wasm and the outside world. At the Ruby side, that would require either creating specific JS-aware adapters for HTTP clients or framework components (e.g., a custom JS-aware generation provider for Active Agents), or monkey-patching HTTP internals.

Dealing with CORS is trickier. Browsers block direct HTTP requests from WebAssembly to external origins that don’t set CORS headers. The only workaround is to use an HTTP proxy.

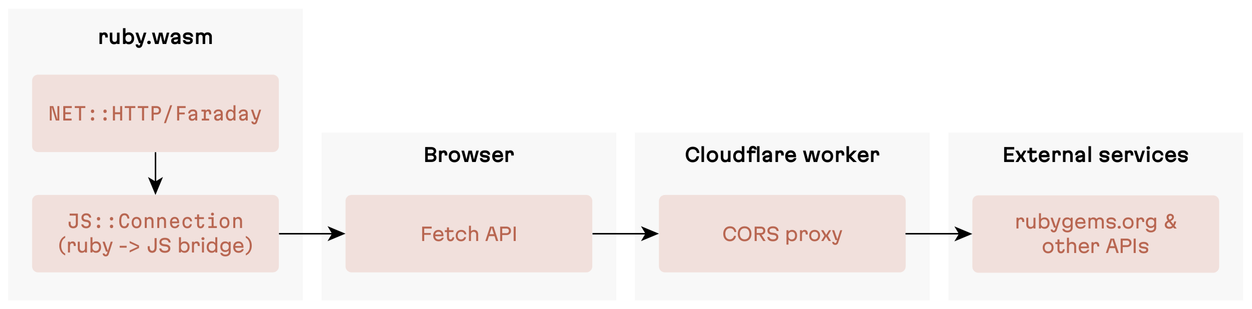

We explored how RunRuby.dev solves these problems to find the right solution for TutorialKit.rb.

RunRuby.dev vs. HTTP

RunRuby.dev implements an HTTP bridging architecture with several key components.

HTTP bridging architecture

First, we have a JS::Connection class—a Ruby-to-JS bridge that executes HTTP requests via the browser’s Fetch API:

# src/stubs/js/connection.rb

class JS::Connection

def proxy_uri(uri)

if URI(uri.to_s).host.match?(/(\A|\.)rubygems.org\z/)

"https://worker.runruby.dev/proxy?#{uri.to_s}"

else

uri.to_s

end

end

def request(uri, req)

js_response = JS.eval(<<~JS).await

return fetch('#{proxy_uri(uri)}', {

method: '#{req.method}',

headers: #{req.to_hash.transform_values { _1.join(';') }.to_json},

body: #{req.body ? req.body.to_json : 'undefined'}

})

.then(response => {

const isOctetStream =

response.headers.get('content-type') === 'binary/octet-stream' ||

response.headers.get('content-type') === 'application/octet-stream';

if (isOctetStream) {

return response.arrayBuffer().then(ab => ({

status: response.status, headers: response.headers,

uint8array: new Uint8Array(ab)

}));

}

return response.text().then(text => ({

status: response.status, headers: response.headers, text

}));

})

JS

# Build Net::HTTPResponse from js_response...

end

endThen, there is also a Faraday adapter for libraries using Faraday for HTTP requests:

# src/stubs/faraday/adapter/js.rb

class Faraday::Adapter::JS < Faraday::Adapter

def call(env)

super

response = JS::Connection.new.request(env[:url].to_s, create_request(env))

save_response(env, response.code.to_i, response.body) do |response_headers|

response.each_header { |k, v| response_headers[k] = v }

end

end

end

Faraday::Adapter.register_middleware(js: Faraday::Adapter::JS)Finally, a RubyGems patch that switches gems downloading to JS::Connection:

# src/stubs/rubygems_stub.rb

Gem::Request.prepend(Module.new do

def perform_request(request)

JS::Connection.new.request(Gem::Uri.redact(@uri).to_s, request)

end

end)What is https://worker.runruby.dev/proxy used by JS::Connection? It’s a Cloudflare worker that implements a simple cross-origin proxy.

What TutorialKit.rb can learn from RunRuby.dev

Patching or extending HTTP clients to work in WebAssembly is doable, no questions here. We can provide examples and ready-made patches for popular HTTP clients.

The proxy requirement is a bigger challenge. We can handle it by one or a combination of the following solutions:

- Provide a public proxy (with security considerations)

- Offer self-deployable proxy templates (Cloudflare worker, Lambda, Cloud functions, etc)

- Document proxy setup as part of tutorial deployment.

The decision on the final solution is yet to be made. And that’s not the only TODO item left in this project.

Future work

The TutorialKit.rb project recently entered its second and final phase (from the grant perspective, we will, of course, continue supporting it after the deadline, given demand from the community).

What’s to be done?

First of all, the current in-progress tasks:

- Complete Action Policy tutorial. This tutorial serves as a reference example for future gem tutorials.

- Finish tarball distribution evaluation. Complete the tarball gems distribution strategy implementation and decide whether to use it instead of the current bundling approach or keep both options for users to choose from.

- Implement HTTP requests support

There are a lot of other potential nice-to-have features that will require more research (and, inevitably, a bit of battle testing). The good news is: the core is already here, and it’s working. From this point on, the job is less about proving the concept, and more about polishing the framework: making builds faster, runtime behavior more predictable, and the author workflow as frictionless as possible.