What we learned from creating PostCSS

12 years ago, we created PostCSS, a CSS automation tool with 400M monthly downloads which is used by Google, Wikipedia, Tailwind, and 38% of developers. In this post, we share what we learned during this long journey maintaining such a popular open source project.

Some history and early lessons

In 2013, I decided I no longer wanted to manually manage vendor prefixes like -webkit- in CSS. At the time, the common solution was to use Sass mixins, but I wanted something more automatic. The best UI is just having your problem solved without any UI. So, I created Autoprefixer, a tool which reads CSS as input and generates new CSS with vendor prefixes.

For that project, I needed a CSS parser and API to work with CSS. And I found Rework by TJ Holawaychuk. The first versions of Autoprefixer were based on Rework (the first name was even rework-vendors).

I quickly found that Rework isn’t enough for Autoprefixer. For instance, I wanted to preserve the original whitespace in CSS to be able to use Autoprefixer as a text editor plugin.

Hire Evil Martians

With open-source tools used by millions like PostCSS and Autoprefixer, we've shaped the landscape of frontend development. And we can help you create products that developers love and rely on daily, too!

Since TJ decided not to add this feature to Rework, I realized I needed to write my own CSS tooling framework.

Lesson −1: Be more cooperative with your big users. At least give them a chance to send you a pull request with a prototype.

Lviv, Ukraine. A few days before the first PostCSS release.

As a result, the first version of PostCSS was released.

I was under a deadline, and a quite unusual one. You see, I had a pre-set date in mind to start on a “digital detox” project (before this term was invented): it would be a full month without touching anything with a CPU to see how it would affect my mind.

As I mentioned in my popular open source guide, popularity is the result of direct efforts. The amount of resources for promotion is comparable to writing the code itself.

with React downloads for comparison](/static/cd6e8bbf462d48c0bfac4f4e9893e00b/ad90d/downloads.png)

The growth of PostCSS downloads with React downloads for comparison

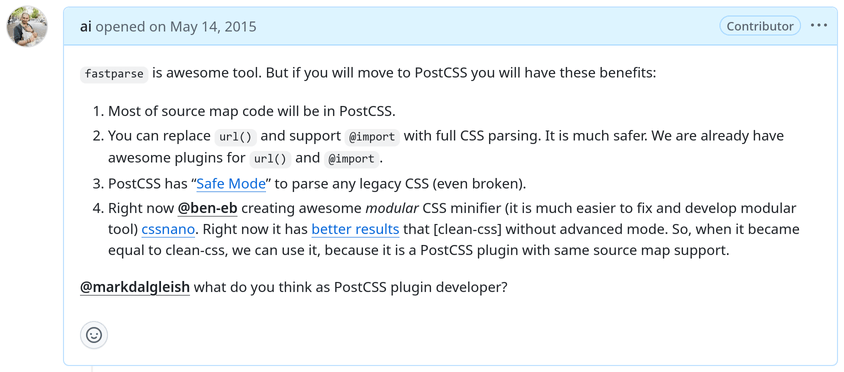

For instance, PostCSS’s popularity got a big push when PostCSS was used as a CSS parser in Webpack. But this was not by chance, I suggested PostCSS to its authors, accompanied with many arguments in favor of doing so.

Or as another example, we spent a whole day polishing the few first sentences of PostCSS’s README.md.

Lesson 0: Don’t forget to reserve a significant amount of time for writing docs and promoting your open source project. Also, don’t hesitate to approach potential clients directly to suggest using your library.

Now, after these 12 years of development, almost all developers are using PostCSS. Even people who don’t use it directly often use it as a dependency (like in Webpack or Vite).

The goal of PostCSS was to help bring new ideas to CSS tools. To help developers experiment with CSS syntax and tooling. Actually, we initially thought about PostCSS as an internal framework just for CSS tooling developers. One that the end‑user should not know about.

But very quickly, we found that developers were afraid of adding any new tool to their frontend build pipeline. By contrast, we found that end‑users were much more willing to add a new plugin to a tool already in their build pipeline.

In the end, this is why we made PostCSS visible to the end‑user. Our goal was to bring CSS tooling diversity. So we decided to be a marketing platform to help CSS tooling address end‑user fears of adding new tools.

Lesson 1: Balance between plugins and built-in features

If you have plugins, provide a full working solution out of the box for most users. Only people with unique needs should disable/enable plugins.

By default, PostCSS does nothing. For it to do any work, you need to add a specific plugin, like Autoprefixer, Tailwind CSS, postcss-preset-env, or postcss-mixins.

There are two issues with this approach: people don’t like to make choices, and most projects need the same features anyway.

As a result, PostCSS users always complain about struggling with this huge plugins list without knowing what they need.

Compare this with amazing Lightning CSS, which already has basic features built in (like polyfills, bundling, and minification) and requires plugins only for specific use cases.

A similar example is Vite vs. Webpack. Vite just works out of the box for most cases, and webpack needs to be configured even for the most standard use case.

This reminds me of good practice from Ruby on Rails: Convention over configuration. Suggest some defaults for users; don’t ask them to define everything.

But it doesn’t mean that everything should be built-in. PostCSS has gotten a lot of benefits from the plugin architecture:

- The PostCSS core was tiny; it is much easier for me to support it alone.

- Instead of a massive project with many developers and conflicts, we split into a few projects with their own teams: core, CSS polyfills, minificator, and so on.

- Plugins are a great way to do a lot of interesting experiments in CSS tooling, like

postcss-easing-gradients, which was even transformed into a CSSWG draft proposal. - Plugins are essential, not only for public experiments, but also for unique, in-house needs in specific projects. For instance, in my projects, I often have a few custom plugins that are impossible to make universal.

- Dev tools always need some flexibility, as every project has unique needs.

Lesson 2: Don’t be afraid to be too late

Right after I had created my two most popular projects, people told me the projects were too late and outdated.

Just after a few versions of Autoprefixer, the Chrome team announced that they would not be adding any new vendor prefixes. At this point, I even thought about giving up and abandoning my project altogether. Yet, even 12 years later, Autoprefixer still has 100M monthly downloads.

Likewise, shortly after PostCSS was started, CSSWG announced CSS Houdini, a project to make CSS in the browser more flexible. A lot of people told me that nobody will need PostCSS because people will do CSS automation in browsers with these new APIs. 12 years later, CSS Houdini isn’t finished (at least in the form that those commentators expected back in those days).

So, don’t be afraid of AI replacing your tool or other competitors. The only thing that can really demonstrate the real market is how it plays out in practice. New tech may not be as helpful as promised. A new competitor could be too slow to compete. In short, it’s better to create a quick prototype and see the real result.

Lesson 3: For performance, architecture is more important than programming language

PostCSS, written in JS, was 4 times faster than Sass, which was written in C++. Not because JS is a better programming language, but because of better architecture and memory management.

The JS community is poisoned by hype, and big companies often use it. As a result, we’re all thinking in primitive black-white concepts like “C++ is faster than JS” or “everything is faster with Rust”.

Initially, PostCSS was even slower than its inspiration, Rework. But my friend Ravil Bayramgalin converted PostCSS to a proper tokenizer-parser architecture. ≈80% of the parsing time is in the tokenizer, and with this split, he was able to focus optimization on a small part. He then used many clever hacks like using regular expressions for quick jumps through the source string to find a closing ".

I especially want to highlight the importance of memory management in performance. For instance, CSSTree, also written in JS, was about 1.5 times faster than PostCSS at the time, primarily by cleverly reusing objects to minimize calls to the garbage collector.

Lesson 4: Avoid burnout by making sure issues don’t just return

When I close an issue caused by user error, I always try to add a warning, an input check, or a documentation clarification to prevent others from making the same mistake.

For instance, if the issue is simply a misuse of the API, explaining the mistake will not prevent other users from making the same mistake and opening a new issue again. In this case, the best way will be to add a warning to prevent misuse of the API.

PostCSS has a special option to set the parser, but many users put it in the plugins list. I could complain about users and be overwhelmed by the same issues. Instead, I added a special check which will print a warning directly to the user.

if (plugin.parse) {

throw new Error(

'PostCSS syntaxes cannot be used as plugins. Instead, please use ' +

'one of the syntax/parser/stringifier options.'

)

}This really helped me avoid burnout as an open-source maintainer. Fun fact, the source of this idea came from my hobby of reading stories about space engineering.

So, the best way to prevent questions is:

- Add types to prevent the wrong way of using the API.

- Add extra JS code to check API usage.

Adding docs should always be the last step because many users don’t read the docs. But often it is the only option (a huge FAQ section in the Autoprefixer docs is a way to reduce the opening of new issues).

Quick tip: ask the issue creator to fix the docs. This is important because you, as the person who completely knows the tool, are less capable of fixing the docs, because you don’t know how to learn your tool.

Another risk for burning out is the circle of guilt. This is when you have a lot of issues without your answer, so you start blaming yourself, which drains your motivation, leading to an even larger backlog.

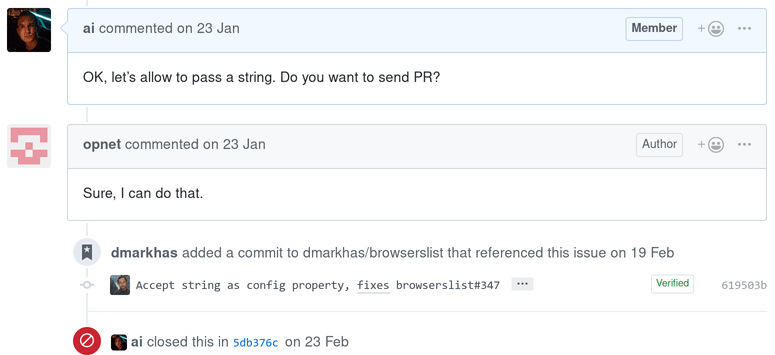

My solution: try to answer quickly, but ask the issue creator to fix the code.

Open source is not just about free support, but about collaboration. Also, a lack of code from your side should not prevent a big problem for your tool’s user to implement a fix themselves, since they know how to write code. The main frustration for users of open-source tools isn’t a lack of immediate fixes, it’s the feeling of being ignored. Once they see that you’ve heard them, they are often happy to contribute a solution themselves.

Lesson 5: Deprecate in the first major release, remove in the next

The best way to make major changes in the API is the tick-tack approach:

- On the first major release, mark the API as deprecated.

- Then, remove this API only in the next major release.

By the way, I took this approach from Ruby on Rails, where it is a common practice.

Of course, it’s not always possible to do it in this way (for instance, we’re removing the old Node.js version in a single major release). But it’s better to try to find a way for it when it is possible.

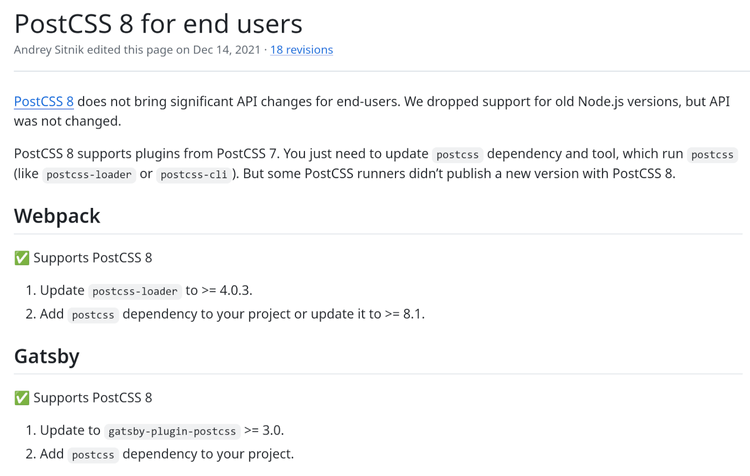

Of course, it is always a good idea to publish a step-by-step migration guide when releasing a new major release, like we did for PostCSS 8.0 API changes.

Migration often requires ecosystem changes. For instance, for many PostCSS major releases, we need some changes in builders like Webpack, Vite, etc. For this problem, it’s always a good idea to create a Wiki page with ecosystem migration status.

On big API changes, it’s a good idea to announce them before the release and create a channel to collect feedback on any potential showstoppers.

For instance, before the PostCSS 8 release, we announced changes in a blog post and on social media.

Lesson 6: Provide best practices to shape the ecosystem

Use guides, examples, and boilerplate to promote good practices and discourage bad ones. Don’t assume that people will discover all the best practices on their own!

We’re very happy that we force every PostCSS plugin to have clear input and output CSS examples. This happened because we created plugin boilerplate and put input/output examples in the template.

We also defined a clear guideline for plugins and runners.

Don’t forget that examples in docs are not just illustrations, but something that forms habits in the community. Use them wisely!

Additionally, people need simple step-by-step guides like we write for plugin development. There is even a section on how to fight with the frustration of plugin development.

Lesson 7: Be friends with your competitors

Don’t be afraid to promote new projects in your field.

Many people think that Sass is a competitor for PostCSS (that is a more complex question, however). But actually, instead of fighting with each other, we’ve had a pretty good relationship.

For instance, I’ve often said that it is possible to use Sass together with PostCSS. We made an agreement on naming and framing to reduce conflicts. We worked together on CSS tooling benchmark to represent each tool correctly.

It ended with the fact that the Sass author moved Google to PostCSS and helped us a lot.

But we were also open to new tools. When CSSTree was released (a PostCSS competitor which is faster than PostCSS), we also promoted them on our social media. When Lightning CSS improved performance and DX, we also told about them.

I personally think that in open source, where we are all working for free, any new “competitor” could just free you from spending your own time on supporting people for free.

Lesson 8: Human touch is important for the community

Try to keep in-person contact with the most valuable developers in your ecosystem, for instance, by sending a postcard or meeting with people.

An ecosystem is not just the code. It’s also the people. Human connections are not just text and processes.

At one point, I wrote to every PostCSS plugin developer, asking for their home address and then sent them a postcard with stickers. Many people liked it. But it has also created a deeper feeling in me about how many people are in the ecosystem. At that moment, an abstract number became something real.

The only problem was that I didn’t spend enough effort to scale postcard sending! One year it was around ≈20, but the following year it increased to ≈100.

Sending a New Year postcard to every developer who made a plugin for PostCSS. It took me 2 weeks to sign them all

Another recommendation: create a note with cities where the most active participants of your ecosystem live. Then, next time you travel there, you can meet with them in person.

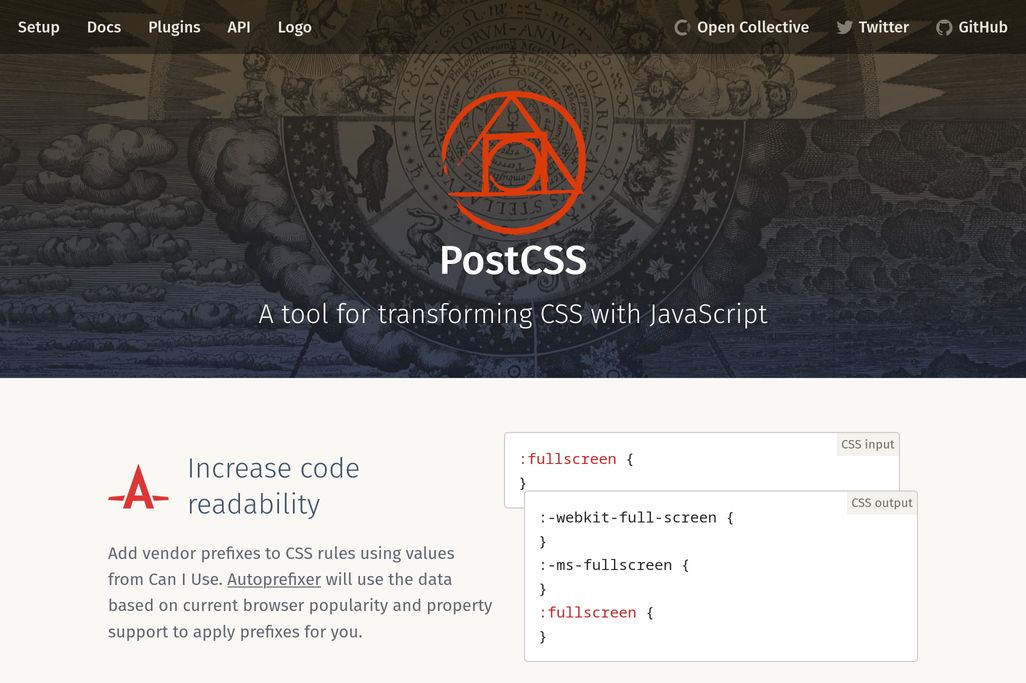

And this next thing is not a recommendation, but it’s something that I personally like to do. Most of my projects have some style behind them. Autoprefixer was about knights (with a knight’s art in release posts, knight’s motto as release names). For PostCSS, we choose the style of alchemy (since every knight has their own Merlin). You can make a great project without a common style behind it. But it has been a lot of fun keeping up with this. For instance, check out the amazing postcss.org design by Andrey Okonetchnikov.

PostCSS website

Small tips for open source maintainers

Finally, a few “controversial” tips to think about but maybe not always follow.

- Try to avoid the build step in your library. Of course, for web apps, it’s almost impossible to avoid a build step. But it’s not so hard to keep your open source library build-free. In PostCSS, we keep sources as vanilla JS files with hand-written

.d.tsfiles (or you can even define types in TypeDoc like Svelte does). Without a build step, users will be able to test pull request just bypnpm add postcss@postcss/postcss#branch. Or you can quickly debug and fix a bug innode_modules/postcssand then copy and paste it back to the repo. - React is bad for static websites like project docs. Use Astro or just static HTML files instead. We tried React for postcss.org and found that React requires significant resources to support it. It is OK for your big web app, but not scalable for small static docs, which you want to visit only once per year.

Evil Martians have made a lot of popular open source projects. If you need help with open source around your projects, write us!